Introduction

The Hetch Hetchy Story represents the oldest unresolved environmental issue in US history. The mainstream media has mostly picked up on the debate as to whether or not to tear down the O’Shaughnessy Dam, yet the real scandal about how conservative allies of Pacific Gas & Electric Company (PG&E) stole hundreds of millions of dollars of electricity produced even in the face of a federal law mandating that all power be distributed using a municipal power system within San Francisco has been hidden from view. Here are some details of this scandal.

The issue of public vs. private control over electricity production in San Francisco has been raging since 1898. It led to a failed national campaign by John Muir and the city’s corporate elite to block the plan to build a dam in Yosemite Park’s Hetch Hetchy valley. Muir’s Sierra Club and activists today are still demanding that the dam be torn down. But that is not the only struggle involving Hetch Hetchy. The other battle is the long censored story about public control of electricity and how private companies have resorted to lies and political propaganda to bury the issue. Even though the dam and water system have recently been updated, the real scandal that relates to the dam involves PG&E and how it used its political influence to take control over its power production from 1925 on-wards. The story represents an epic example of private theft of public resources like no other.

Thanks to the work of J.B. Neilands, a former professor at UC Berkeley, the SF Bay Guardian revealed the story of this theft in 1969 – and built up a public education campaign over time that led activists to call for the development of public power services as required in the 1913 Raker Act that originally allowed the dam to be built. More important, it reopened the legal requirement of the city’s own Charter of 1898 for public ownership of all utilities.

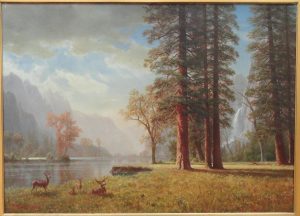

The Hetch Hetchy Battle falls into a number of major time periods. The first period runs from 1880 to 1901 during the time when San Francisco was starting to really grow, demand for water escalated. The Spring Valley Water Company private control of the city’s drinking water angered citizens. Investigations for new supplies was split between two camps, those calling for public development as a common resource on one side and on the other, the Southern Pacific elite that had control of the Spring Valley. The Spring Valley plan was to build an irrigation canal from Lake Tahoe while San Francisco’s mayor James Phelan decided on a plan to build a reservoir at Hetch Hetchy soon after San Francisco passed its new City Charter. The political phase of the battle within the city was to follow.

The San Francisco Labor Party took control of the city in 1901 and shelved the plan. However, following the 1906 earthquake, investigations showed that the Labor Party’s boss, Abe Ruef had received bribes including one from Spring Valley insiders to accept the Tahoe plan. Ruef, the mayor and the Board of Supervisors would be driven from power. A new administration would take over and win public funding for Hetch Hetcy in 1907. After San Franciscans voted to finance the plan the city then had to fight a national battle led by the Spring Valley Company and John Muir, but would finally gain federal rights at the end of 1913 with the passage of the Raker Act.

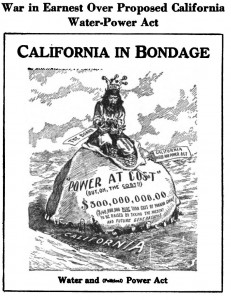

The next phase of the project, the construction phase took nearly two decades to finish (all work was completed in 1934). 1922, during the peak of this phase that a far larger political battle over water and power took center stage around water and power throughout the entire state. That year proposition 19 called for the state to build an operate a publicly owned water and electric system. The ballot lost after one of the largest privately funded campaigns in state history led by PG&E and its allies. Many more attempts took place but all failed until President Roosevelt took office in 1932 and went ahead with the creation of the massive Central Valley Project.

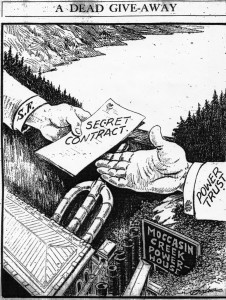

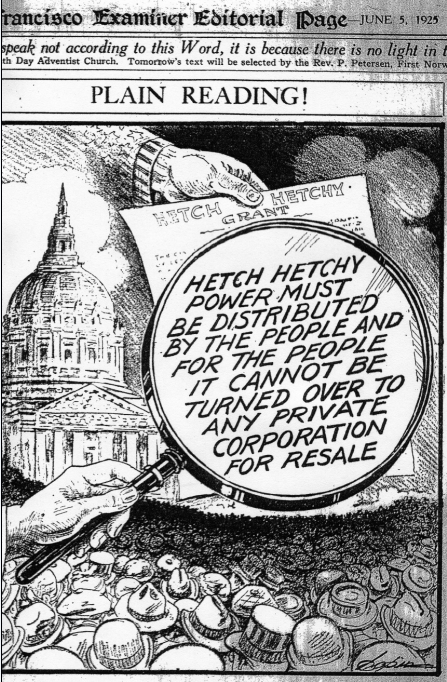

But in 1925, following the completion of Hetch Hetchy’s electric system, out of the blue, just as power lines had been run up to its private substation in Fremont, PG&E staged a national media circus with the help of its political allies to win control over Hetch Hetchy’s power. Following a week long convention by the National Electric Light Association with its keynote speaker being Herbert Hoover, the San Francisco Board of Supervisors voted to break the specific requirements of the Raker Act by letting PG&E take over sale and distribution of Hetchy power. For the next 15 years, angered citizens fought to reverse the illegal deal and finally won a brief respite with the U.S. Supreme Court ruling of 1941.

The battle would resurface briefly after World War II with PG&E and the city cutting a new deal, burying the issue until the late 1960’s when J.B. Neilands and the SF Bay Guardian would bring the scandal back into the public eye. Thanks to the SF Bay Guardian the issue would take on major prominence in the late 1980’s and launch a new era calling for the end of private control over electricity.

The two tabs open the Bay Guardian’s extensive timeline describing what happened and contain an excerpt of J.B. Neiland’s original piece from 1969 covering the scandal. The Fourth tab includes the best online resources backing up the issue, most of it culled from the mainstream media, which only covers whether or not the dam should be torn down, omitting aspects they found too hot to handle. As such, it offers only a segment of the state’s public power battle long censored by history.

Timeline

Power struggle chronology | SF Bay Guardian | January, 1997

How the best-laid plans of John Edward Raker and the U.S.

Congress were scuttled by Pacific Gas & Electric:

A chronology, 1848-1997

Editors note: For almost 25 years, the Bay Guardian has been investigating and reporting on the Raker Act scandal. It has never been an easy job: The mayor, the supervisors, and the city attorney have consistently refused to release key documents on the history of the city’s relationship with Pacific Gas & Electric (PG), and PG has consistently refused to release anything. (2016 Note: The battle to take back Hetch Hetchy power did not end in 1997. The movement continued for years and only recently slowed down, partly due to the Bay Guardian being sold and then closed.)

This summer, political editor Tim Redmond, who wrote his first PG

story back in 1982, was assigned to take a different approach. He

flew to Washington, D.C., and spent two weeks poring over records

in the Library of Congress, the U.S. Supreme Court, the National

Archives, and the Interior Department library. He came back with

more than 1,000 pages of documents, some of which shed important

new light on the issue. The original memos and notes of former

Interior secretary Harold Ickes, for example, show that the

federal government very nearly moved in 1941 to revoke the city’s

grant and take over the Hetch Hetchy dam.

What follows is a chronology of some major events in the history

of the Raker Act scandal. In most cases, the information comes

directly from primary-source material that Redmond compiled in

Washington. Savannah Blackwell wrote the chronology from 1988 to

1997. Copies of all the major documents are available for

inspection at the Bay Guardian office.

May 1848: Sam Brannan returns from a secret visit to John

Sutter’s sawmill in Coloma and, having carefully cornered the

local market on picks, shovels, and pans, marches through the

streets of San Francisco shouting “Gold!” and waving a quinine

bottle half full of the precious dust, scooped from the banks of

the American River. Within a year, San Francisco has become a

boomtown; gold-crazy miners arrive from all over the world. They

quickly discover that the city has plenty of bars, brothels, and

fly-by-night banking establishments, but very little freshwater.

In fact, some find it’s cheaper to send their soiled clothes by

boat to Hawaii than to get them laundered in town.

1898: The private Spring Valley Water Co. has gained monopoly

control of water service in San Francisco, but the limited

rainfall runoff that feeds its tiny reservoir system can’t

possibly keep pace with the needs of a growing city. After

crossing off 15 alternative sites, Mayor Phelan files in April

1902 for water rights on the Tuolumne River with money from his

own pocket. City engineer Grunsky devises a plan to dam Hetch

Hetchy Valley in Yosemite National Park and pump the water 200

miles to San Francisco. Although there were better sites for

water, Hetch Hetchy Valley, a granite-walled canyon formed like a

mammoth water tank, rising 2,500 feet above a flat meadow floor,

was chosen because of its enormous potential to produce cheap

electrical power. For the next decade, four different Interior

secretaries seesaw back and forth on S.F. demands to use Hetch

Hetchy Valley as a city reservoir.

April 18, 1906: A massive earthquake sets off a series of

devastating fires that burn out of control. Firefighters are

paralyzed when Spring Valley’s cheaply built private water mains

prove inadequate and critical hydrants go dry. Pressure mounts

for a publicly owned water-distribution system.

1912: With Spring Valley’s private water rates continuing to

rise, and service as poor as ever, city officials press Congress

to give San Francisco a radical and unprecedented federal grant:

the right to construct a municipal water dam inside a national

park. John Muir is furious, and rages: “Dam Hetch Hetchy? As well

dam for water tanks the people’s cathedrals and churches; for no

holier temple has ever been consecrated to the heart of man.” He

has founded the Sierra Club to fight the proposal, and

congressional preservationists line up against it.

1913: Rep. John Edward Raker from the state’s third district,

which includes Yosemite, breaks the impasse with a historic

compromise. The Raker Act (HR-7207) would allow San Francisco to

build its dam – but only on one condition: The dam must be used

not only to store water but also to generate electric power,

which must be sold directly to the citizens through a municipal

power agency at the cheapest possible rates. The bottom line:

Like public water, public power would free San Francisco from

what Rep. Bailey called “the thralldom … of a remorseless

private monopoly.”

The Raker Act includes language requiring formally that San

Francisco accept the grant, with all its conditions, before

breaking ground on the dam. It states that if the city fails to

live up to those conditions, the grant reverts to the federal

government. The Board of Supervisors passes a resolution agreeing

to abide by the terms of the law.

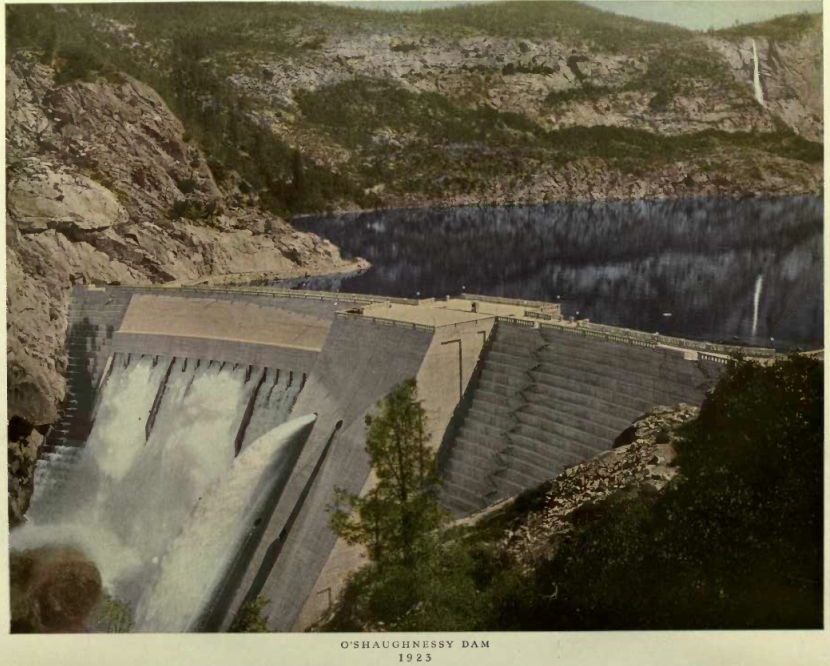

1923: Under the leadership of the brilliant engineer M.M.

O’Shaughnessy, San Francisco builds a tremendous dam on the

Tuolumne and an innovative, gravity-fed system of underground

pipes that can carry the fresh mountain water under the Central

Valley, the East Bay hills, and the Bay, and into the city’s

reservoirs. The Spring Valley franchise is revoked. City workers

begin repairing old mains, laying new ones, and creating a

municipal water department.

The city also builds a hydroelectric powerhouse at Moccasin

Creek, where Hetch Hetchy water is diverted through giant turbine

generators, and buys enough copper transmission wire to stretch

from the Sierra to San Francisco. While the transmission lines

are being built, the city agrees to sell the electricity from

Moccasin to PG.

In May 1923, the National Park Service gets wind of the deal and

begins to investigate. The investigation concludes that the deal

is illegal under the Raker Act, but the solicitor general of the

Interior Department declines to take action, saying that the

arrangement is only a temporary measure to avoid letting all that

power go to waste while the city finishes building its own

transmission lines and local distribution system.

1925: Transmission lines are strung all the way to the South Bay,

when suddenly the city announces that it has run out of money and

can’t do any more construction. The city’s power line ends just a

few hundred yards from a PG substation in Newark – which

conveniently connects to a new high-voltage cable PG has just

completed from Newark to San Francisco.

On July 1, 1925, since the city lacks not only a final

transmission line but the local facilities to distribute its own

power, city officials agree, as another temporary measure, to

sell the Hetch Hetchy electricity at wholesale rates to PG, which

then sells it to local customers at retail. The city makes a few

million dollars off the deal; PG makes a fortune.

The remaining copper wire is stashed in a warehouse and

eventually sold for scrap. Every supervisor who votes to approve

the contract is thrown out of office in the next election.

1927: The supervisors place a general-obligation bond act on the

city ballot to raise the money to buy the utility poles, wires,

meters, and other equipment the city needs to set up a municipal

power system.

PG campaigns vigorously against the bond measure, claiming it

will raise taxes. The Chamber of Commerce and most of the local

newspapers follow the PG line. City officials make only a

halfhearted effort to support the bonds. In the end, 52,215 vote

in favor of the measure, and 50,727 against – but since the city

charter requires a two-thirds majority for general-obligation

bonds, the proposal fails.

1930: In September, Interior Secretary Wilbur writes to Mayor

Rossi and asks what the city is doing to comply with the Raker

Act. Rossi agrees to meet with Wilbur in December, and the two

work out a three-year plan that will lead to San Francisco’s

creating its own public-power agency.

The supervisors place another bond act on the ballot. PG spends

the unprecedented sum of $21,153.71 on a successful campaign to

defeat it. Rossi’s three-year plan gathers dust.

Ultimately, nine bond proposals will go before the San Francisco

voters. PG will mount a high-priced campaign against every one,

and with no effective leadership from city officials to promote

the benefits of public power, every proposal will be defeated.

1933: President Roosevelt appoints Harold Ickes secretary of the

interior. Ickes learns of the 1923 Park Service investigation

into San Francisco’s power sales to PG, and asks his solicitor

general to look into the situation and see whether anything has

changed.

Aug. 24, 1935: Ickes issues a detailed opinion concluding that

the city’s contract with PG is a clear violation of the Raker

Act. He urges the city to revoke the contract and move with all

dispatch to establish a municipal power system. Mayor Rossi

acknowledges receipt of the ruling and tells Ickes he’s referring

the matter to the city’s Public Utilities Commission.

March 9, 1937: After repeated warnings from Ickes, Rossi and the

supervisors place a charter amendment on the ballot authorizing

the city to sell $50 million in revenue bonds to establish a

municipal power system. Unlike previous general-obligation bond

measures, the revenue bonds will have no impact on local taxes

and will be repaid entirely from public-power revenues. The

measure once again fails – largely, Interior Solicitor General

Frederic Kirgis concludes, “due … to lack of support by the

Mayor and his failure to campaign for it.”

On March 11, Ickes sends Rossi a cable giving the city 15 days to

convince him it is serious about complying with the Raker Act.

When no such assurance arrives, he instructs the U.S. attorney

general to file suit. Rossi immediately sends a cable to

Washington begging Ickes to delay legal action and asking for

another conference. Ickes wires back that for two years he has

“patiently tried to persuade San Francisco to obey the mandate in

a law which it originally concurred in, but without success,” and

tells Rossi he sees no point in further discussion. “Apparently,”

Kirgis notes in a memo to Ickes, “the Mayor was completely

bewildered and disconcerted by the knowledge of the fact that

conferences and delays would no longer be the regular order of

things.”

April 11, 1938: Federal judge Michael J. Roche rules in favor of

Ickes, concluding that San Francisco’s contracts with PG violate

the Raker Act’s ban on sales of Hetch Hetchy power to a private

corporation. The law states that in the case of any attempt by

the city to “sell, assign, transfer or convey” Hetch Hetchy power

to a private corporation, the grant “shall revert to the

Government of the United States.” Ickes, however, decides not to

ask for a forfeiture ruling in the hope that San Francisco will

accept the court’s mandate and comply with the act. Roche issues

an injunction forbidding the city to continue selling power to

PG, but suspends enforcement for six months to give city

officials time to come up with an alternative plan that the

Interior secretary will find acceptable. Ickes announces that

he’s “ready to consider any proposals officials of San Francisco

might have to offer.”

Instead, the city appeals. Rossi vows to fight all the way to the

Supreme Court if necessary and says that “if worst comes to worst

… the city should move for amendment by Congress of the Raker

Act.”

Sept. 13, 1939: The 9th Circuit Court of Appeals overturns

Roche’s decision, concluding, as the city’s attorneys have

argued, that as long as the San Francisco voters refuse to

approve a bond act for municipal distribution facilities, the

city has no choice but to let PG act as its “agent” for the sale

of electric power. Ickes instructs the Attorney General’s Office

to file an appeal with the U.S. Supreme Court.

April 22, 1940: The Supreme Court rules 8-1 in favor of Ickes and

directs Judge Roche to reinstate his injunction. Justice Hugo

Black, for the majority, unequivocally rejects the city’s

position. “Congress,” he notes, “clearly intended to require – as

a condition of its grant – sale and distribution of Hetch Hetchy

power exclusively by San Francisco and municipal agencies

directly to consumers in the belief that consumers would thus be

afforded power at cheap rates in competition with private power

companies, particularly Pacific Gas and Electric.” Black

dismisses the city’s technical arguments in support of the 1925

contracts with a terse phrase: “Mere words and ingenuity of

contractual expression, whatever their effect between the

parties, cannot by description make possible a course of conduct

forbidden by law.”

Black’s opinion acknowledges that city voters have refused to put

up the money for a municipal distribution system and admits that

the courts have no right or authority to tell the citizens of San

Francisco how to spend their money. However, he explains,

Congress has every right to attach conditions to a grant of

federal land – and if the city, for whatever reason, fails to

live up to those conditions, the federal government has the right

to revoke that grant. He quotes the comments of Sen. Walsh of

Montana during the Raker Act debate: “We are making a grant of

rights in the public lands to the city of San Francisco, and we

may impose just exactly such conditions as we see fit, and San

Francisco can take the grant with those conditions or it can let

it alone.”

The ruling concludes that “the city accepted the grant by formal

ordinance, assented to all the conditions … and up to date has

utilized the rights, privileges and benefits granted by Congress.

Now the City seeks to retain the benefits of the Act while

attacking the constitutionality of one of its important

conditions.”

The Chronicle and Examiner both blast the decision, lampooning

Ickes and congressman Frank Havenner, who supports public power,

as tyrants determined to force their will on the people of San

Francisco. Both papers run editorials asserting that the city is

best served by continuing to sell its power to PG and that Ickes’

position amounts to an attempt to take away the millions of

dollars in annual revenue the city receives from the PG

contracts. Only the San Francisco News reports the truth: Every

other city that runs a municipal utility finds public power very

lucrative, and the potential gains to San Francisco from

complying with the Raker Act make the annual payments from PG

look like bird seed.

May 6, 1940: A group of San Francisco businessmen, led by Chamber

of Commerce president Walter Haas, announces plans to push

Congress to amend the Raker Act and eliminate the city’s

public-power mandate. Rep. Richard Welch agrees to introduce the

amendment, and Sen. Hiram Johnson agrees to support it. The Welch

bill never even makes it out of committee.

May 21, 1940: Ickes meets with Mayor Rossi, City Attorney John

O’Toole, Board of Supervisors president Warren Shannon, and

Utilities Manager E.G. Cahill in Washington and warns that if

they don’t quickly come up with a plan to comply with the Raker

Act, he’ll move to revoke the grant and take over the dam. “You

would be here on a much better footing,” he tells them, “if the

record of delay, evasion and double-crossing hadn’t been what it

has been on the part of officials of San Francisco.”

Cahill insists that PG “has seen the handwriting on the wall” and

that something could be worked out, given time. “Yes,” Ickes

replies, “all you want is time until I’m out of office…. I have

always believed that a man can be fooled once, but a man is a

damn fool who allows himself to be fooled a second time, and this

isn’t only the second time.”

July 23, 1940: Rossi, O’Toole, Shannon, and Cahill travel to

Washington again for a second conference with Ickes. Cahill

presents a new plan: The city, he suggests, can lease all of PG’s

local distribution facilities and hire the company’s local sales,

repair, and service staff for a flat annual fee. Then the city

can use those facilities to sell Hetch Hetchy power. In the wake

of the Supreme Court decision, Cahill says, PG has accepted the

deal. He presents a copy of a draft lease contract signed by the

company’s president, J.V. Black.

Ickes asks Cahill if the contract includes an option to purchase

the facilities. Cahill says the company offered that option, but

only at a cost that made the entire lease deal far too expensive

to be feasible.

Ickes studies the contract, and on July 25, he tells the city

that he’s willing to go along with a lease, but that the language

of this deal still gives PG too much control over Hetch Hetchy

power. The San Francisco officials promise to go back and

renegotiate. If PG won’t offer a better deal, Rossi promises, a

new bond issue will go before the voters on the next possible

ballot. Ickes agrees to ask Judge Roche to suspend his injunction

again, to give the city a few more months.

April 1941: The city sends Ickes a new lease contract proposal.

Ickes asks Leland Olds, chair of the Federal Power Commission, to

review it; Olds concludes that it’s a terrible deal. “It is clear

that the proposed arrangement not only does not offer the city

the advantages of public distribution of Hetch Hetchy power,” he

writes, “but may even have the effect of freezing high rates.”

May 22, 1941: Ickes holds another conference with city officials

and points out the problems with the lease contract. Rossi and

O’Toole freely admit that it’s not a good deal for the city and

that it includes excessive charges and fees. They tell Ickes they

submitted it anyway, because it was the best deal they could get

from PG. When Ickes rejects the contract and threatens to enforce

the injunction and begin steps to take back the dam, Rossi begs

for another delay. He says that he’s finally prepared to make the

case to the voters in favor of a municipal buyout, and will try

another bond act in November.

Ickes agrees to ask Judge Roche to hold off another year, until

the summer of 1942 – but only if Rossi and San Francisco’s civic

leaders promise to vocally support the bond act and campaign

strongly for its passage. The Chronicle and Examiner immediately

accuse Ickes of extortion and claim he’s trying to “gag” civic

organizations like the Chamber of Commerce and the Downtown

Association. Both groups announce they’ll oppose the bond act and

organize a high-powered campaign committee to work for its

defeat. Organized labor, on the other hand, comes out strongly in

favor of the buyout plan. Nearly every union in town endorses it,

and prominent labor lawyer George T. Davis signs on to chair the

proÐpublic power campaign.

Ickes travels to San Francisco to campaign for the bond act. When

chamber officials try to meet with him, he reminds them how much

money they’ve received from PG and tells them to take a hike.

November 1941: Just a few weeks before the bond election, PG

announces a sweeping reduction in local electric rates. The

Chronicle carries the story on the front page. The bond act goes

down to defeat, under another avalanche of adverse publicity and

PG money.

Ickes informs Mayor Rossi that he has no choice but to begin

moving to revoke San Francisco’s Raker Act grant and take over

the Hetch Hetchy dam.

Dec. 7, 1941: Japanese airplanes attack Pearl Harbor in a

stunning, predawn strike, thrusting the United States into World

War II. The War Department quickly looks for ways to redirect the

nation’s electric power supplies to essential wartime industries.

March 1942: The War Production Board orders San Francisco to sell

to the Defense Plant Corp. the entire output of the Hetch Hetchy

power project for an aluminum-smelting factory that is under

construction at Riverbank, near Modesto. Ickes approves the plan,

citing the strategic importance of aluminum to the war effort. He

also notes that the factory site will be close to the city’s

existing transmission lines, allowing the power to be carried

directly from Hetch Hetchy to the factory without PG acting as

middleman. Judge Roche suspends his injunction again, this time

for the length of the contract between the city and the Defense

Plant Corp.

All further talk of enforcing the Raker Act is temporarily

drowned out by the roar of the cannons and the hum of giant

factories turning plowshares into swords.

June 1944: Financial problems and mismanagement bring production

at the Riverbank aluminum plant to a virtual halt, and the War

Department prepares to shut it down. Judge Roche prepares to

reinstate his injunction, but San Francisco files a motion to

once again suspend it while the city finds a new way to dispose

of its public power. On June 26, Roche holds a hearing on the

petition and chides city officials for their constant attempts to

use delaying tactics to evade the law. He then agrees to continue

the matter until August, when the city promises to come forward

with another new plan.

Arthur Goldschmidt, director of Interior’s Power Division, warns

Ickes that the “Hetch Hetchy problem [is] again rising in San

Francisco.”

August 1944: Mayor Roger Lapham sends Ickes an entirely new

proposal. It calls for PG to deliver over its lines from Newark

enough Hetch Hetchy electricity to supply all of San Francisco’s

municipal services – the Muni railway, the street lights, General

Hospital, etc. That would amount to about 200 million kilowatt

hours a year. In exchange, the city would allow the company to

keep all the remaining output of the Hetch Hetchy project – about

another 300 million kilowatt-hours a year – and sell that power

to its own customers as it saw fit.

Undersecretary Abe Fortas, filling in for the vacationing Ickes,

rejects the proposal. An increasingly angry Judge Roche gives the

city one more chance to come up with a better plan.

December 1944: Mayor Lapham writes to Ickes with the rough

outlines of yet another proposed solution to the Hetch Hetchy

“problem.” This time, the city proposes to pay PG an annual

“wheeling fee” for transmitting enough Hetch Hetchy power from

Newark to San Francisco to supply the municipal service needs.

The Turlock and Modesto irrigation districts, a pair of rapidly

growing public-power agencies, would buy as much of the remaining

power as it could handle, and resell it to their own customers.

Ultimately, Lapham insisted, Modesto and Turlock would be able to

purchase everything the city couldn’t use. In the meantime, PG

would buy any surplus, or “dump,” power to avoid letting it go to

waste.

Ickes thanks Lapham for his letter, reminds him that a final,

detailed plan is due by the end of the year, and warns that the

Interior Department “will not participate in any evasion of the

law, however complex or ingenious. I hope that your leadership

will not, this time, have to waste time, energy and newsprint in

the fruitless pastime of beating the devil around the PG bush.”

January 1945: Ickes writes Mayor Lapham to inform him that the

proposed Turlock-Modesto-PG contracts are not acceptable. “The

proposed agreements,” he notes, “do not carry out the intent of

the Congress in the Raker Act, which was designed to bring

City-owned power, over the City’s transmission and distribution

system, directly to the citizens of San Francisco.” He agrees

that selling the city’s power to Turlock and Modesto, which are

public agencies, might comply with the “letter” of the law. The

big problem, as always, was the role of PG. He reminds Lapham

that Judge Roche’s final extension will expire on March 1.

On Jan. 24, Lapham arrives in Washington and spends four days

meeting with Undersecretary Fortas. With Ickes’ approval, Fortas

suggests an alternative plan: If Lapham would place a policy

declaration on the next local ballot binding the city to

acquiring its own power distribution system – and agree to

campaign actively for the passage of that measure and a bond

issue to carry it out – Ickes would support a congressional

amendment suspending the prohibition on sales to PG for a period

of five years.

Lapham tells Fortas that he’d consider placing the policy measure

on he ballot, but says he “could not at this time commit myself

to an active campaign on behalf of the bond issue.”

June 11, 1945: San Francisco modifies its power contracts again,

slightly. This time, the city agrees to pay PG a wheeling fee for

transmitting municipal power and agrees to provide Turlock and

Modesto with as much additional power as they can buy. The

surplus would be carried on PG’s lines – again, at a fee – to a

handful of major PG customers, including Permanente Metals and

Permanente Cement, who would pay the city directly for the

service. But only when Hetch Hetchy power generation was

particularly high, and the needs of Turlock, Modesto, and

Permanente were low, would any “dump” power be sold directly to

PG, and even then, the amounts would be insignificant. The

contracts would run until 1949.

A frustrated Ickes concedes that, as a practical matter, he has

limited options. The nation is in the midst of a severe postwar

energy shortage, and if he were to take over the dam, no other

federal agency would be in a position to use its power. He

acknowledges that, under the circumstances, he can’t find solid

grounds to oppose the latest arrangement in court. But he notes

that “the plan, while technically feasible, does not carry out

full intent of the Raker Act” and warns that it “does not appear

to assure substantial compliance with the Raker Act beyond 1949.”

He urges Judge Roche to maintain jurisdiction over the matter and

says his department “would oppose present approval of the plan

with respect to the years following 1949.”

He also insists that Modesto and Turlock sign agreements never to

resell their Hetch Hetchy power to PG.

July 9, 1945: City Attorney Dion Holm appears before Roche to

argue that the 1938 injunction – which is still in effect – is

too strict, since it bans the city from ever selling any power to

PG. Roche denies San Francisco’s petition for suspension or

amendment and orders that the injunction become final and

permanent.

1946: President Truman fires Ickes, who has become increasingly

bitter and unhappy with his job, and replaces him with Oscar

Chapman.

November 1946: The General Accounting Office investigates the new

Hetch Hetchy contracts, concludes that the sale of “dump power”

to PG is probably illegal, and suggests that the federal

government demand an accounting of all past sales to PG and take

legal action to make the city repay its ill-gotten gains. The

comptroller general forwards the GAO report to Chapman, who sits

on it for two years.

January 1948: San Francisco files its annual report with the

Interior Department, which reveals that more than 5.6 million

kilowatt-hours of Hetch Hetchy electricity were sold to PG in

1947. Walter Seymour, director of Interior’s Power Division,

writes a memo to Chapman noting that “certainly, the sale of this

amount of power to the Pacific Gas and Electric Company is a

violation of the Raker Act.” The memo goes on to state that the

federal government could enforce the court injunction and block

further PG sales, but “under the existing conditions of the

shortage of power and the scarcity of fuel, it seems to me that

an action which would result in the wastage of water power would

be unwise.”

Soon, Seymour advises, the federal Central Valley Project will

have completed a transmission line to Tracy and will be in a

position to take over the Hetch Hetchy power output. Meanwhile,

he concludes, “the distribution of energy beyond Newark … will

have to be made by the Pacific Gas and Electric Company, until

the City builds a distribution system.”

Dec. 22, 1948: After repeated memos from the Comptroller

General’s Office, Chapman directs Assistant Secretary Krug to

respond to the 1946 General Accounting Office report. Krug

concedes that the contracts appear to violate the Raker Act but

says that, under the circumstances, “it would be inappropriate at

this time to recommend to the Attorney General that he institute

suit.”

Feb. 9, 1950: The comptroller general writes to the Justice

Department anyway, informing the attorney general that he

disagrees with Interior’s position. He suggests that “action

should be instituted either (1) to enjoin further performance

under the existing arrangement … (2) to declare forfeit the

rights of San Francisco under the Raker Act … and (3) to

recover … the amount received by San Francisco under the

illegal 1925 contract.” The attorney general does nothing.

Aug. 28, 1950: San Francisco begins negotiating an extension of

the 1945 contracts. Michael H. Strawn, commissioner of the Bureau

of Reclamation, reviews the proposal and writes to Chapman to

complain that Interior, in tacitly approving the city’s actions,

“in effect confesses and condones operations both outside the law

and in contradiction to the strong public power policy that the

Secretary of the Interior has followed in the same area in

Reclamation matters.” He suggests that, if the city won’t provide

its own distribution system, Chapman move to take control of

Hetch Hetchy and transfer the power to the Central Valley

Project, which has facilities that are “virtually complete” to

handle the electricity.

Sept. 1, 1950: Ickes, still concerned about the issue, writes to

Chapman with charges that San Francisco is continuing to violate

the Raker Act and urges him to take action. Chapman responds that

he is “fully cognizant of the fact that there has not been a

strict compliance with the [law].” However, he notes: “Thus far,

as you well know, the City and County of San Francisco has not

been able, through the vote of the people of that political

subdivision, to acquire the distribution system necessary to

distribute all of the Hetch Hetchy power. Nor is there any agency

of the federal government which is able to distribute this

power.”

1954: San Francisco approves a new set of contracts with PG and

Turlock and Modesto, which will run for 33 years, until 1987.

1955: Rep. Clair Engle presents evidence to a congressional

committee proving that Turlock and Modesto have been reselling

Hetch Hetchy power to PG, violating the express agreement Ickes

insisted on in 1945. Federal Power Commission figures compiled by

Engle show that, between 1945 and 1953, more than 10 percent of

the Hetch Hetchy power bought by Turlock and Modesto has been

resold to PG. The Interior Department, which seems to have

abandoned all interest in enforcing the Raker Act, pays no

attention whatsoever.

1964: Joe Neilands, a biochemistry professor at UC Berkeley,

joins a campaign against PG’s plan to build a nuclear power plant

at Bodega Bay. He runs into Frank Havenner, who tells him that

the nuclear project is awful but that nothing compares to the PG

Raker Act scandal. Neilands, who has never heard of the Raker

Act, is intrigued. He calls James Carr, the new general manager

of the San Francisco Public Utilities Commission, and asks when

the city plans to enforce the 51-year-old law. Carr tells him

that “it is premature to discuss municipal distribution of power

in San Francisco.”

1965: Neilands writes to Frank Barry, the Interior Department’s

solicitor general, who tells him that “we know of no means by

which the U.S. can require the city to acquire the municipal

distribution system.”

1969: Neilands compiles his research and submits it to the Bay

Guardian, which publishes his story under the headline “How PG

Robs S.F. of Cheap Power.” When the Bay Guardian confronts Oral

Moore, general manager of the PUC, he says the city has no plans

to enforce the Raker Act.

1972: At the request of the San Francisco Neighborhood Legal

Assistance Foundation, a group of pro bono CPAs called

Accountants for the Public Interest conducts a study of the

financial potential of public power in San Francisco. The

accountants conclude that the city could clear $22 million a

year, after all costs, by buying out PG’s distribution system and

running a municipal utility. The group urges the PUC and the

Board of Supervisors to commission a full-scale, independent

feasibility study. Not one supervisor is even willing to request

a hearing on the matter.

1973: The San Francisco civil grand jury investigates the Raker

Act scandal, concludes that the city is required to operate its

own public-power system, and asserts that the contracts with

Modesto, Turlock, and PG are “of questionable legality.” The

daily newspapers ignore the report, and it winds up gathering

dust on a City Hall shelf.

1974: Attorney Richard Kaplan and neighborhood activist Charlie

Starbuck file suit in federal court, charging that San Francisco

is in violation of the Raker Act. A district judge throws it out

of court, concluding that Starbuck, as plaintiff, has no standing

to sue for enforcement of the Raker Act. By law, only the

secretary of the interior and the San Francisco city attorney

have the right to pursue that action. Kaplan and Starbuck appeal.

1977: The 9th Circuit Court of Appeals rejects the Starbuck and

Kaplan case, confirming the lower court ruling that a San

Francisco citizen lacks standing to sue. The appellate judges,

however, make a point of stating that they don’t find fault with

Starbuck’s factual claims. If anything, the ruling seems to

continue the federal courts’ record of agreeing that San

Francisco is breaking the law.

1979:Yale University Law School graduate Ralph Cavanagh joins the

Natural Resources Defense Council (co-founded in 1970 by John

Bryson, another graduate of Yale law school who is now CEO of

Southern California Edison). Cavanagh focuses on electric

utilities, particularly in the Pacific Northwest. According to

the Pittsburg-based Heinz Foundation, which gave a $250,000

public policy award to Cavanagh in 1996, “(Cavanagh)’s goal was

to improve the alignment of shareholders and societal interests,

so that utility profits no longer were linked primarily to

promoting increased electricity use.”

1982: A citizen group called San Franciscans for Public Power

puts an initiative on the ballot that would force the city to

conduct a feasibility study on municipalizing PG. PG spends

$680,000 – a local record – funding a misleading campaign headed

by Mayor Dianne Feinstein to defeat the measure. Among the few

prominent supporters of the public-power initiative is

Assemblymember Art Agnos, who holds a press conference outside

PG’s headquarters to denounce the company’s blatant attempt to

“buy San Francisco’s vote.”

1983: Just weeks after the public-power initiative goes down to

defeat, PG officials contact the City Attorney’s Office to start

renegotiating the power-sale contracts, which are due to expire

in 1985. Talks begin in secret at PG headquarters, with lawyers

from the company and the City Attorney’s Office trying to hash

out a new long-term agreement. PG wants to raise the rate it

charges San Francisco for “wheeling” power along company lines

and for “firming” service, which backs up the city’s power supply

when rainfall is low and the generators at the dam aren’t

producing at their optimal levels. Since the recent public-power

measure has gone down to defeat, the city has no real leverage to

use as a bargaining chip against PG. Facing the prospect of

millions of extra dollars in PG fees, the city’s negotiating team

decides to raise the rate that San Francisco charges the Turlock

and Modesto irrigation districts for Hetch Hetchy power.

September 1984: The general manager of the Turlock Irrigation

District, Ernest Geddes, finds out what San Francisco and PG are

up to, and asks Rep. Tony Coelho for help. Coelho, who has become

one of the most powerful Californians in Congress, invokes the

Raker Act: The city, he says, is supposed to sell power directly

to the citizens at the lowest possible cost. Since San Francisco

doesn’t have a municipal utility of its own, he argues, that

provision ought to apply to sales to Modesto and Turlock, which

are public-power agencies. Just to be sure, he introduces a bill

that would force San Francisco to sell Hetch Hetchy power to the

irrigation districts at cost – in other words, for almost

nothing.

Mayor Feinstein realizes that the bill will probably pass and

that the city will be in a bind. Unless the sales to the

districts bring in fairly substantial revenues, it will be hard

to defend the whole concept of “disposing” of Hetch Hetchy power

outside the city, and new pressure for a municipal utility could

emerge. A longtime ally of PG and a foe of public power,

Feinstein quickly contacts Coelho and cuts a deal: Coelho agrees

to withdraw the bill, but Feinstein has to promise to sell almost

two-thirds of the Hetch Hetchy output to the districts, at

favorable rates, every year until 2015. The city negotiators go

back to the table to continue their talks with PG, with less

leverage than ever.

May 1985: The City Attorney’s Office briefs the Board of

Supervisors in secret session on the outlines of the emerging

power-sale deals and asks the board to approve “the basic

principles” of a new set of 30-year contracts. The board votes

6-0, on roll call, to approve the deal, with no public discussion

or debate, and to accept “interim” two-and-a-half-year contracts

while final talks continue. The negotiators go back to work out

the fine print.

June 1987: Staffers at the city’s Public Utilities Commission and

the City Attorney’s Office argue in internal memos that PG is

asking for completely unreasonable terms in the final contracts,

fee hikes that would cost the city millions. The company refuses

to compromise, and talks break down. Finally, Feinstein

personally intervenes, meeting privately with PG chair Richard

Clarke and hashing out a contract that nobody outside PG thinks

is a good deal for the city. In essence, it requires the city to

keep paying PG millions of dollars a year for “wheeling fees,”

guarantees Turlock and Modesto access to more than half the

city’s Hetch Hetchy power, and effectively sabotages any new

attempt to create a municipal power system.

Fall 1987: Interior Secretary Donald Hodel becomes the latest

federal official to threaten San Francisco with the loss of its

Raker Act grant. He proposes to study tearing down the dam and

restoring Hetch Hetchy Valley. The Sierra Club, among other

environmental groups, strongly endorses the concept – after all,

club members say, the city never kept its end of the 1913 deal.

But Hodel never pursues the matter seriously, and it quickly

dies.

1988: On New Year’s Eve, the newly elected mayor, Art Agnos, is

summoned to PG headquarters to meet with Dick Clarke, who tells

him the facts of life: PG controls enough votes on the Board of

Supervisors to block any effort at promoting public power. The

contracts can’t be changed and will never be stopped. And if

Agnos doesn’t want to play ball, PG will crush his political

career.

The city’s budget analyst reports that the contracts are a bad

deal and a violation of standard city procedures and takes the

unusual step of recommending that the supervisors not approve the

deal. A Guardian analysis shows that San Francisco is losing more

than $150 million a year to PG by failing to comply with the

Raker Act and establish a municipal utility.

But the board votes 8-3 to go along with PG for another 37 and

1/2 years, and Agnos, the onetime public-power advocate who

campaigned as an alternative to the pro-downtown politics of the

Feinstein era, signs the contracts into law.

Just a few weeks later, Agnos announces that the city’s budget is

facing a shortfall that could approach $100 million. He warns

that services may be cut dramatically, that small businesses,

Muni patrons, and kids who go to the zoo will have to pay higher

prices to keep the city in the black.

Not once does he mention PG.

1989: As co-director of the NRDC’s energy program, Ralph Cavanagh

becomes the key implementer of the “California Collaborative”

which supported the notion that environmentalists should sit

behind closed doors at the table with private utilities to iron

out their differences and hammer out energy efficient programs to

be run by private utilities. Cavanagh later states publicly that

he regretted the term, because “collaboration still has has

overtones of Vichy, France.” See “Transforming a Mega-Utility”

from In Context, fall 1992.

1991: Energy Foundation is created and founded by the Pew

Charitable Trusts, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur

Foundation and the Rockefeller foundations with a $20 million

budget over three years. Hal Harvey is named Executive Director.

The Energy Foundation states that its mission is to “influence

energy decision-makers at the point of decision.” The intitial

report shows the foundation’s full support of energy efficiency

programs run by private utilities (called “Demand side managment”

(DSM) programs. “A utility executive is unlikely to pursue

efficiency aggressively if his or her company cannot generate a

fair return on its investment,” the initial 1991 report states.

Among 49 other groups, the Energy Foundations grants money to a

consumer advocate group called The Utility Reform Network, but

ends the group’s funding in 1993.

1993: Energy grants $14,000 for nine months to the aggressive

Washington, D.C.-based Environmental Action Foundation, which

fought at the federal level the private utilities’ demand that

their customers pay the full cost of their lost investments. The

same year, Energy grants to EA an additional $80,000 for two

years.

Sept. 22, 1993: The Bay Guardian publishes “A City Held Hostage,”

a report by Tim Redmond that points out that the city is losing

millions of dollars a year by failing to bring its own Hetch

Hetchy public power to the city. Also, Redmond writes, the city

risks losing the Hetch Hetchy dam by failing to comply with the

federal Raker Act of 1913. That act says that, in exchange for

the right to dam the Hetch Hetchy Valley in Yosemite National

Park, the city “shall develop and use power for the use of its

people.” Actually, the city’s public-power agency, Hetch Hetchy

Water and Power, supplies power to about 1,300 government

entities, including the City Attorney’s Office. But the rest of

Hetch Hetchy’s power gets dumped in Turlock and Modesto. No San

Francisco residents or businesses benefit from the cheap power

generated by the dam — power that is rightfully theirs. Instead

the city pays about $25 million annually to PG for the private

utility to “wheel” (carry) power into San Francisco. Redmond’s

article also discusses a 1940 Supreme Court decision that

determined that San Francisco’s deal with PG was illegal and

issued an injunction ordering the city to establish a

public-power system. The city has essentially ignored the

injunction, although it still stands.

Jan. 12, 1994: Bay Guardian reporter Martin Espinoza exposes the

National Park Service’s plan to hand over the valuable Presidio

electrical system to PG — and then pay the company more than $12

million to take it. The entire deal violated federal bidding

laws. Officials from the city public power agency, Hetch Hetchy

Water and Power, show no interest in supplying power to the

Presidio. In fact, Espinoza reports, Hetch Hetchy general manager

Larry Klein told Park Service officials in 1992 that the

department was not interested in running the system.

Jan. 31, 1994: In the wake of the Bay Guardian’s revelations that

the Park Service was trying to give the Presidio contract to PG,

Supervisor Angela Alioto calls on the San Francisco Public

Utilities Commission to bid for the contract.

Feb. 16, 1994: Public-power advocates urge the city to bid for

the Presidio’s electrical system. But Anson Moran, general

manager of the Public Utilities Commission shows his stripes when

he tells the board’s Select Committee on Base Closures that

selling power to the Presidio could be “too political.”

March 15, 1994: The National Park Service agrees to give San

Francisco’s public-power agency a chance to bid for the Presidio

power contract (RFP) but releases a request for proposals that

virtually guarantees PG will win; the RFP calls for the bidders

to operate a system that PG has designed. The Park Service admits

that the RFP was based in part on information provided by PG (see

“At PG’s Bidding,” 3/23/94).

March 30, 1994: Despite his public statements that the PUC would

prepare an “aggressive bid” for the Presidio contract, PUC chief

Moran privately works to undermine the effort. In a confidential

memo to Mayor Frank Jordan, obtained by the Bay Guardian, Moran

urges Jordan to veto Alioto’s resolution calling for public power

at the Presidio.

April 1, 1994: Mayor Jordan vetoes Alioto’s Presidio public-power

bill. Alioto allies cry foul (see “Good News, Bad News,” 4/6/94).

May 2, 1994: The Board of Supervisors unanimously overrides

Jordan’s veto and approves Alioto’s resolution urging the city to

bid for the takeover of the Presidio electrical system (see “PG’s

Nightmare,” 5/4/94).

Aug. 4, 1994: In a major concession to public pressure, the

historically PG-friendly PUC agrees to bid on a contract for the

Presidio electrical system (see “PG Gets Competition,” 8/10/94).

Aug. 8, 1994: Hetch Hetchy Water and Power submits its bid for

the Presidio system, marking the first time the agency has ever

competed with PG for a contract. But it fails to bring up the

point that PG had no franchise agreement with the city to provide

power there; it also fails to cite the Raker Act.

Sept. 29, 1994: Despite competitive bids by the city of San

Francisco and two other bidders, the Park Service awards the

power contract to PG.

Oct. 13, 1994: Under immense pressure from Alioto and

public-power advocates, City Attorney Louise Renne files a

protest with the General Accounting Office in Washington, D.C.,

to stop the Park Service from awarding the Presidio electrical

contract to PG.

Oct. 31, 1994: The Board of Supervisors votes to raise the PG

franchise fees from 0.5 percent to 2 percent of the utility’s

gross revenue for 1995, and then to 4 percent each year after

that (a rate still below the national average and less than half

of what some cities charge). The increase would bring more than

$21 million yearly into the city’s General Fund.

It would also balance the high fees PG charges the city for

wheeling Hetch Hetchy power: in 1994 PG paid the city $2.4

million in franchise fees for delivery of electricity, and the

city paid PG about $25 million in fees for wheeling power into

the city. PG refuses to pay the new rates. The City Attorney’s

Office does virtually nothing to enforce the board’s legislation,

claiming that PG has won a court injunction barring the increase.

That, it turns out, is untrue: in June 1996, at a public hearing,

Deputy City Attorney Michael Olsen admits to Alioto that no

injunction had ever been issued.

Nov. 7, 1994: Reacting to the surge in public-power activism,

Angela Alioto, as president of the Board of Supervisors, proposes

a special committee to pursue ending PG’s illegal monopoly in San

Francisco and bringing cheap public power to residents. PG

lobbies hard against the proposal, but Alioto succeeds in getting

the board to narrowly approve the creation of the Select

Committee on Municipal Public Power. Alioto notes that, at a time

when the city was closing health clinics because of budget

shortfalls, the potential revenue that could come from

municipalization is too attractive to ignore.

Jan. 12, 1995: The Select Committee on Municipal Public Power

votes to spend $150,000 on a preliminary study of whether the

city should take over PG’s distribution system.

Jan. 12, 1995: In the wake of Bay Guardian revelations that the

city controller and the chief administrative officer had never

performed an annual audit of PG’s franchise agreement — even

though the 1939 franchise deal required such audits — City

Controller Ed Harrington announces that his office will perform

the first audit of PG franchise-fee payments. Harrington defends

the city’s lack of prior enforcement by saying, “There are a

variety of items in the administrative code that aren’t being

done by the city.” The city’s chief administrative officer, Rudy

Nothenberg, is also required by the code to file reviews of PG

compliance with the franchise agreement. But he writes in a

letter to the board that he can’t get involved in financial

issues with PG because his wife works for the utility. The Bay

Guardian later discloses that Nothenberg owned between $20,000

and $200,000 in PG stock.

1995: Environmental and consumer groups sign on to the

“framework” a set of principles to guide utility deregulation in

California. According to members of the groups involved, Cavanagh

did not support the section that said that utilities should be

given “substantially less than” full recovery of stranded costs.

Energy gives a two-year $100,000 grant to the Alliance for

Affordable Energy in New Orleans. It stops funding the group

after the group had to abandon a collaborative approach.

Energy grants the Environmental Action Foundation $75,000 for one

year, but at the same time works with the NRDC to create “Project

for a Sustainable FERC Energy Policy,” a group of organizations

led by an NRDC staffer. “Project” takes a much softer approach to

the private utilities in discussions of electric utility

deregulation at the federal level and undercuts the aggressive

approach of Maryland-based Environmental Action Foundation, which

eventually shuts it doors due to financial problems.

Jan. 17, 1995: The Board of Supervisors votes 7 to 3 to ask Mayor

Frank Jordan to spend $150,000 on a preliminary feasibility

study. Jordan vows to fight the expenditure.

Jan. 18, 1995: The Bay Guardian reports that Republicans in

Washington are aiming to foreclose on the city’s right to operate

and control the Hetch Hetchy dam. The Republicans charge that San

Francisco is violating the Raker Act because none of the Hetch

Hetchy power goes to San Francisco residents (see “Power Loss,”

1/18/95).

Jan. 20, 1995: Mayor Frank Jordan, whose reelection campaign will

rely heavily on financial and political support from PG and its

allies, writes a letter to the board indicating his plan to veto

the supervisors’ legislation requiring a feasibility study (see

“Pulling the Plug,” 2/8/95).

Feb. 15 1995: The General Accounting Office in Washington, D.C.,

dismisses City Attorney Renne’s protest of the awarding of the

Presidio contract to PG as “untimely” and upholds the Park

Service’s decision. In essence, the GAO rules that Renne’s office

missed the filing deadline for contract protests.

Feb. 17, 1995: City Controller Ed Harrington releases the first

audit of PG’s franchise-fee payments. In the audit, conducted

only for 1991 through 1993, Harrington finds that PG owes the

city $114,276 for using city streets to deliver electricity and

gas to the Presidio for the period from Jan. 1, 1991, through

Dec. 31, 1993. PG refuses to cooperate, declining to give the

city documents that are key to determining if the utility is

accurately and fairly calculating how much it owes in franchise

fees.

The audit also finds that in a random sampling of bills, PG

overcharged local customers by a total of $514,130. On the advice

of the City Attorney’s Office, Harrington refuses to audit PG for

the years prior to 1991 and also fails to go after fees owed on

other military bases, including Hunters Point and Fort Mason,

since 1939. His decision may have kept the city from collecting

millions of dollars. Renne’s office says it has no way of knowing

how much the city is owed for the years 1939 to 1992 (see “Cover

Up?” 2/22/95).

March 20, 1995: In a first real step toward complying with the

Raker Act, the Board of Supervisors votes 8 to 2 to require the

PUC to conduct a $150,000 preliminary feasibility study. The

ordinance includes language stating that if any city officials

try to block the study, they will be guilty of “official

misconduct,” which is grounds for removal from office (see “PG

Loses a Big One,” 2/22/95).

April 5, 1995: The Board of Supervisors unanimously decides to

urge the PUC to sue to overturn the Park Service’s decision to

give the Presidio contract to PG (see “One Forward, Two Back,”

4/5/95).

May 24, 1995: Without publicly announcing the move, City Attorney

Louise Renne files suit against PG and the federal government in

an attempt to overturn the Park Service’s multimillion-dollar

giveaway of the Presidio contract. The suit alleges that PG

should have been disqualified because it had designed the system

it then bid on. The city attempts to lay out how the Park Service

rigged the bid for PG. Once again, both daily newspapers black

out the story (see “S.F. Sues Feds, PG” 5/21/95).

May 24, 1995: PG files suit in state court against San Francisco

to block the city’s attempt to collect millions of dollars in

franchise fees the utility owes for delivering power to the

Presidio. Public-power advocates call the suit a “preemptive

strike.” The city countersues in what Harrington says is a way

for the city to collect on franchise fees owed on the Presidio

since 1939. But the City Attorney’s Office never attempts to use

the suit to break the original 1939 franchise, although

public-power advocates contend that PG’s failure to pay franchise

fees on the Presidio is grounds for ending the agreement (see

“Power Offensive,” 5/31/95).

July 5, 1995: The Bay Guardian reports that Jordan has

effectively killed funding for the preliminary feasibility study

by ignoring the PUC’s request for the money until after the

deadline for inclusion in the 1996 budget (see “Jordan Backs PG,”

7/5/95).

July 17, 1995: Alioto outfoxes Jordan by replacing $150,000 (to

cover the study) from $375,000 in proposed cuts to the PUC’s

budget.

Nov. 22, 1995: The Bay Guardian reports that the PUC, whose

request for proposals did not require bidders to address the

Raker Act, has selected a firm to conduct a preliminary

feasibility that has ties to PG. Strategic Energy Limited’s

manager of Western operations, Phillip Muller, worked for PG for

13 years before resigning only two years ago (see “Fox Guards

Henhouse?” 11/22/95).

Dec. 18, 1995: After the Bay Guardian discloses mistakes in the

scoring of various bidders, the Select Committee on Municipal

Public Power formally asks the civil grand jury to investigate

the irregularities in the bidding process that led to the

selection of Strategic Energy Limited (see “Lights On?”

12/20/95).

Dec. 19, 1995: The PUC terminates Strategic Energy Limited’s

contract. Hetch Hetchy general manager Larry Klein admits to

making a “couple errors in judgment”: namely, not telling the

commission that two losing bidders had protested a disputed

scoring process.

January through March 1996: Alioto and public-power advocates

have trouble getting the PUC to set up a technical review

committee for the study that would include citizens interested in

municipalization. In fact, Klein tries to put John Madden, the

city’s chief assistant controller, on the committee. Madden owns

as much as $100,000 worth of PG stock and helped defeat a 1982

campaign for a feasibility study by providing an inflated,

PG-generated figure for the purchase price of the distribution

system. Renne even says at one point that creating such a

committee would violate the city charter. Eventually the PUC

relents, establishes the committee, and allows a representative

of San Franciscans for Municipal Public Power to join it.

April 1, 1996: Alioto asks Renne for a review of the city

attorney’s long-standing position that the city’s dispersal of

Hetch Hetchy electricity is in technical compliance with the

Raker Act. This is a key question: For decades, the City

Attorney’s Office has relied on a series of internal opinions

that effectively trumpet the PG line that the Raker Act doesn’t

require public power in San Francisco. The Supreme Court has

determined otherwise in clear language — but because the city

attorney is the only local official with the authority to enforce

the Raker Act, the pro-PG opinions have been a roadblock (see

“Power Struggle,” 9/22/93). Alioto never gets a new opinion (see

“Alioto’s New PG Salvo,” 4/3/96).

May 6, 1996: The technical review committee (TRC) selects J.W.

Wilson & Associates of Washington, D.C., a firm with 20 years of

experience consulting with municipal systems, to perform the

feasibility study. Wilson had done two feasibility studies — in

Gilbert, Ariz., and Page, Ariz. — that led to successful

municipalizations. Economic and Technical Analysis Group (ETAG),

another bidder whose president said the firm’s members had

performed $1,000 worth of work for PG, was not chosen.

May 28, 1996: Under lobbying pressure from PG, three PUC

commissioners — Victor Makras, Dennis Normandy, and Marion Otsea

— award the contract to ETAG, despite protests by Wilson and

public-power advocates. ETAG discloses to PUC staff that members

of the firm have performed at least $140,000 worth of work for PG

instead of stressing that point, PUC staffer Larry Klein includes

in the packet to the commissioners an article critical of Wilson.

In September PG discloses to the San Francisco Ethics Commission

that Sam Lauter and Larry Simi discussed the choice of contractor

with those three commissioners during that time (see “The Big

Fix,” 6/5/96, and “The Trouble with ETAG,” 10/16/96).

June 7, 1996:The Thoreau Center, including the Energy

FoundationÕs offices, open at the Presidio.

June 10, 1996: The Board of Supervisors unanimously passes a

resolution urging Mayor Willie Brown to urge the PUC to terminate

the contract with ETAG and award the contract to Wilson. Brown

takes no action on the resolution, thereby making it official

board policy. The PUC ignores the legislation.

June 25, 1996: After discussing the matter in closed session, the

PUC reconfirms its selection of ETAG. Commissioners do not

formally respond to protests made by Wilson and San Franciscans

for Municipal Public Power’s Joel Ventresca, a member of the

technical review committee.

June 30, 1996: The civil grand jury issues its annual

investigative reports but makes no mention of Alioto’s request

for an investigation of the PUC. However, the Bay Guardian later

learns that a strong report critical of the close relationship

between PG and the PUC was not released by the grand jury (see

“The Shame of San Francisco,” page 14).

July 24, 1996: The Bay Guardian reports that of the three members

of the eight-member TRC that did not choose Wilson, Klein gave

Wilson the lowest score. He gave ETAG high marks. The Bay

Guardian had to threaten legal action to get the scoring sheets

disclosed (see “Turning on the Lights,” 7/24/96).

Mid-August to October 1996: Klein informs Alioto that delivery of

the preliminary feasibility study will be delayed until Jan. 15,

1997, about one week after Alioto will be forced by term limits

to leave office. Klein says delays in the selection process, due

to the protest of ETAG’s selection, made it impossible for the

firm to meet the deadline. Klein’s move is illegal, as the Board

of Supervisors must approve any changes to the ordinance, which

requires delivery of the study by Oct. 30, 1996.

September, 1996:Governor Pete Wilson signs California Assembly

bill AB1890 – which deregulates the electric utility industry on

January 1, 1998, and allows utilities to fully recover the cost

of money lost in power plant development from ratepayers. The

NRDC, the first environmental group to sign on, supports the

move. Declaring it a consumer rip-off, CALPIRG protests the

passage of the bill. franchise-fee payments for 1994 and 1995. He

finds that PG owes the city $18,218 for using city streets to

deliver electricity and gas to the Presidio for the period from

Jan. 1, 1994, to Sept. 30, 1994. (PG started remitting

franchise-fee payments for the Presidio Oct. 1, 1994.)

Sept. 24, 1996: City Controller Ed Harrington releases an audit

of PG franchise-fee payments for 1994 and 1995. He finds that PG

owes the city $18,218 for using city streets to deliver

electricity and gas to the Presidio for the period from Jan. 1,

1994, to Sept. 30, 1994. (PG started remitting franchise-fee

payments for the Presidio Oct. 1, 1994.)

Sept. 26, 1996: At a select committee meeting, Alioto makes

another attempt to raise the yearly fees that PG pays for the

right to transmit gas and electricity across city property. She

proposes to raise the fee from 1 percent to 4 percent for natural

gas and from 0.5 percent to 2 percent for electricity. The City

Attorney’s Office maintains that the franchise agreement cannot

be changed.

Oct. 16, 1996: The Bay Guardian publishes “The Trouble with

ETAG,” which reveals that the firm had never completed a

municipalization study. That means the company failed to meet a

key requirement for winning the contract. The firm also

misrepresented the credentials of one of its key members and

claimed falsely to have worked for TURN (The Utility Reform

Network, a consumer-advocacy group). In addition, ETAG president

Ronald Knecht gave a pro-PG deposition during a municipalization

battle between the investor-owned utility and the Sacramento

Municipal Utility District (SMUD) in 1988. Knecht valued PG

facilities at more than three times what SMUD and PG eventually

agreed on. ETAG’s study is released Oct. 11, and public-power

advocates find it biased against municipalization. The study

finds that municipalization will only bring a 0 to 5 percent

savings in rates.

Mid-October to mid-November 1996: Three members of the TRC —

Eugene Coyle (senior economist with TURN), Robert Lehman (San

Franciscans for Tax Justice), and Joel Ventresca — slam the ETAG

study, finding that it is pro-PG and that it downplays the

advantages of public power. In addition, the American Public

Power Association sharply criticizes the report and says it

misses the key advantages of municipalization — namely, more

local control, lower costs of operation, and lower rates.

Oct. 25, 1996: Judge Vaughn Walker decides the Presidio case in

favor of the federal government and PG. The order is filed under

seal, and the city does not object. By losing the case, the city

loses a $50 million contract and a chance for a public-power

beachhead.

Nov. 27, 1996: The Bay Guardian reveals that the Presidio case is

lost and threatens legal action to make the decision public.

Walker rejects all of the city’s arguments. The city fails to

raise the issue of the Raker Act. After the Bay Guardian and

Alioto begin making inquiries about the case, the city attorney

appeals (see “Lights Out,” 11/27/96).

Nov. 27, 1996: The select committee votes to call for a full

feasibility study. Meanwhile, the Bay Guardian reveals that

numerous community organizations — such as the Mission

Neighborhood Center and Kimochi — receiving money from PG have

written to supervisors asking that a full feasibility study be

killed (see “Lights Back On?” 12/4/96).

Dec. 11, 1996: Under pressure from PG, the budget committee’s

Barbara Kaufman and Tom Hsieh table Alioto’s feasibility study.

The move is unusual; it means that Alioto, the legislation’s

sponsor, cannot vote on the issue because under term limits she

will be out of office. Alioto vows to take the study out of

committee and put it to the full board for a vote. “For shame,”

Alioto says to Kaufman and Hsieh (see “PG’s Supervisors,”

12/18/96).

Jan. 1, 1997: After Walker’s judgment is opened to the public,

the Bay Guardian reports the key reason for the loss: Renne

failed to file the protest on time (see “Presidio Power Outage,”

1/1/97).

Jan. 6, 1997: Alioto’s last day in office. She brings the

feasibility study up for a full vote Jan. 13 (see “Kicking and

Screaming,” 1/8/97).

Jan. 8, 1997: Newly minted president Barbara Kaufman kills the

Select Committee on Municipal Public Power.

Jan. 13, 1997: Supervisors kill Alioto’s feasibility study by an

8 to 2 vote. Leslie Katz, Jose Medina, and Leland Yee all break

campaign pledges to the Bay Guardian to support the feasibility

study and vote against the ordinance. Also voting for PG are

Supervisors Amos Brown, Barbara Kaufman, Susan Leal, Mabel Teng,

and Michael Yaki. Only Supervisors Tom Ammiano and Sue Bierman

vote in favor (see “Power Drain,” 1/15/97).

Jan. 29, 1997: Public-power advocates mount a campaign to defeat

Louise Renne in the 1997 election so that a city attorney willing

to enforce the Raker Act can be elected. In addition, Ventresca

prepares to file a complaint with the Ethics Commission over

ETAG’s shoddy report and the PUC’s refusal to select the firm

recommended by its technical review committee. The Bay Guardian

submits the entire scandal to the grand jury. Public-power

advocates also plan to put a measure on the 1997 ballot calling

for either the enforcement of the Raker Act or a complete

feasibility study. Alioto plans to publish a book later this

spring dealing with city corruption and based on Dante’s Inferno.

The title is Straight to the Heart. One whole chapter — and one

whole level of hell — will be devoted to the PG scandal.

June 19, 1997: In the first time PG is brought up on criminal

charges, a Nevada county jury finds PG guilty of criminal

negligence which lead to the 1994 Rough and Ready fire. The fire,

which wiped out 500 acres of land and burned 12 homes, was caused

by overgrown tree limbs touching high voltage power lines. The

Utility company is responsible for keeping the tree limbs at a

safe distance from the power lines. Amoung the extensive paper

trail showing The company’s understanding of the problem prior to

the fire were studies authorized in 1987,1991,1992, and 1995

documenting the severe backlog of trees needing to be trimmed.

Nevada county deputy District Attorney Jenny Ross presented

evidence that despite several supervisors complaining about a

backlog of tree-trimming and insufficient funds to do the work,

PG diverted 80 million dollars in money collected from consumers

from its tree-trimming budget to company profit. The jury who’s

foreman said they wanted to send a message that the company “must

change the way top management makes its decisions,” found PG

guilty of 739 out of 743 criminal charges that were filed against

the company. The utility is now a convicted criminal. State

regulators and a federal court fine the company for issues

related to failure to trim trees away from power lines.

July 21, 1997:The Board of Supervisors votes to settle the city’s

Presidio power suit against PG for $132,494. The settlement

forgives PG’s illegal use of city property to deliver power to

the Presidio and forfeits tens of millions of dollars in

franchise-fee and penalty payments the utility owes the city. Not

one of the dozens of activists and environmental groups out at

the Presidio, or funded by foundations based at the Presidio,

utters a peep of protest.

August 7, 1997:California Senate bill 477, which implements the

issuance of customer-backed bonds to pay off the private

utilities’ lost investments in nuclear power plants, is passed.

Once again, NRDC provides key support. scandal.

Sellout