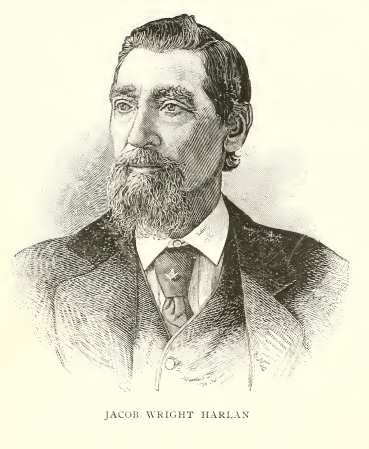

The following piece is from Jacob Wright Harlan’s diary and book titled California, ’46 to ’88.

Chapter 24, pg. 108

Based on his detailed commentary, Jacob probably arrived in the Redwoods in May of 1847, took a month to chopped a redwood tree into 15,000 shingles, which made him $75. This was followed by a paid job for Willaim Ledesdorf of cutting down additional trees which were used in San Francisco to fence off property for Leidsdorf, Fremont and others worth $500. The full book is online here.

I determined to go to the redwood forest on the east side of the San Antonio range of hills to eastward of the present site of East Oakland, and there try to make shingles. I was entirely unacquainted with this kind of work, yet I could but try it, so I hired Richard Swift and went to work. We cut down a very large redwood tree and worked it up into fifteen thousand shingles, which occupied us one month. I then had them hauled to San Antonio landing, now East Oakland, and shipped them on a flat boat to San Francisco, where I sold them to William A. Leidesdorff for five dollars a thousand. I then paid Swift his wages and all expenses and had fifty dollars left. In this way I first became acquainted with Mr. Leidesdorff. He was a native of the Danish island of Santa Cruz, W. I., and, I believe, had a slight dash of negro blood in his veins. He had a hotel on the southwest corner of Clay and Kearny streets, opposite the plaza, and was the most enterprising business man in the town.

I determined to go to the redwood forest on the east side of the San Antonio range of hills to eastward of the present site of East Oakland, and there try to make shingles. I was entirely unacquainted with this kind of work, yet I could but try it, so I hired Richard Swift and went to work. We cut down a very large redwood tree and worked it up into fifteen thousand shingles, which occupied us one month. I then had them hauled to San Antonio landing, now East Oakland, and shipped them on a flat boat to San Francisco, where I sold them to William A. Leidesdorff for five dollars a thousand. I then paid Swift his wages and all expenses and had fifty dollars left. In this way I first became acquainted with Mr. Leidesdorff. He was a native of the Danish island of Santa Cruz, W. I., and, I believe, had a slight dash of negro blood in his veins. He had a hotel on the southwest corner of Clay and Kearny streets, opposite the plaza, and was the most enterprising business man in the town.

At this time there were four stores, or principal mercantile houses, in San Francisco. Melius & Howard were on the corner of Sacramento and Montgomery streets; Robert Parker was on Clay street between Kearny and Montgomery streets; D. L. Ross was on the corner of Montgomery and Washington streets; and William H. Davis and Hiram Grimes were on the corner of Montgomery

and Jackson streets. That is as nearly as, in my memory, I can locate the places of those merchants. The town had begun to grow a little; its population might be about three hundred. Lumber was scarce and not easily to be got. It had all to be sawed by whip-saws, as there were then no saw-mills in the country. Most of the lumber came from the redwoods in the San Antonio hills—back of what is now East Oakland. Lumber sold in San Francisco at about fifteen dollars per thousand feet.

After disposing of my shingles, Leidesdorff asked me if I would take a contract to fence in sixteen fifty vara lots in San Francisco belonging to Commodore Sloat, Commodore Stockton, Colonel Fremont, and some others. The fence was to consist of two rails, with mortised posts, and a space of three feet between the rails. He said their object was to prevent squatters from occupying the lots, and that he would pay me fifty dollars for fencing each lot. I thought well of this, and we entered into a written agreement on the above terms, in which there was no limit of time mentioned for the completion of the work.

I went to San Jose and found David Williamson, that had nearly got us both captured at Santa Barbara. He was working in Oliver’s grist-mill and earning two dollars and a half a day. I showed him my contract and told him what I had done, and asked him to be my partner in the work. At first he hesitated, saying that he was in good employment, earning certain wages, and that my job might be a failure. I said, “All right, David; we will see,” and I mounted and rode off; but presently he called me back and said he would join me. We then hired Swift and went to the redwoods, where we cut down trees and split them into posts and rails. I then bought two yoke of oxen and a wagon, and hired my cousin Joel Harlan to help me to haul the stuff to San Antonio for shipment to San Francisco.

While we were hauling, Williamson was in the city mortising the posts, and as soon as we got them all over to the city, I went there with the team to finish the work. There was then no way to take wagons and teams across the bay, from what is now Oakland to San Francisco, except by San Jose.

We had our tent on the sand hills on Market street on the lot where the Palace hotel now stands. It was nearly all sand hills about there at that time, with shrub oak bushes all over the neighborhood.

We had no tea or coffee, but Yerba Buena grew in plenty under the bushes. We made tea of it and drank nothing else. I believe that it is more wholesome than coffee or China tea. Then we had beef and slap-jacks. One day a cargo of syrup came from the Sandwich Islands; the casks were brought ashore in lighters and rolled upon the beach out of the way of the tide, there being no wharf then. In rolling the casks the top burst from one of them, and the men set it up on end and left it there. David got syrup by the bucketful, and we had plenty to the end of our job.

We began this work on July 6th and finished it on September 20, 1847, to the satisfaction of Leidesdorff, who duly paid us as agreed. After paying all expenses we had five hundred dollars to divide, and we went to our camp, sat down on our blankets in the deep sand, and made our division. David declared that it was the best strike he had ever made and he was going back to Cincinnati. I tried to get him to stay in California, but he was set on going back, and shortly afterward, Capt. Thompson having gathered a band of wild horses to take to the states, David went with him. One of Thompson’s men killed him on the way back, and David died shortly after reaching home.