Introduction

This is the story about one of the most beautiful parks in the Bay Area. Thanks go to a friend (Cecile) who introduced me to the East Bay’s parks. After spending most of the last ten years in bed due Mercury poisoning, I’ve been able to walk around in what has been called the world’s largest urban redwood forest barely 20 minutes from Berkeley. Just weeks after discovering the existence of Oakland’s Joaquin Miller Park, a magical moment in the park set me on a journey to discover its history and more.

After a few walks on the park’s pleasant trails, I discovered the Big Trees Trail on the east side of what used to be a private ranch owned by the “poet of the Sierras’ Cincinnatus Joaquin Miller. Near the crest of a ridge overlooking the bay, among a grove of redwoods, was an odd plaque embedded in concrete that was all but unreadable. Using a cheap digital camera, I took home over a dozen images of the plaque having no idea what it said as the surface had been badly defaced by graffiti. It became clear that the plaque had been intentionally abandoned by park officials. Even its location near a well organized trail was intentionally blocked by wooden rails that left casual guests unaware of its existence.

After a few walks on the park’s pleasant trails, I discovered the Big Trees Trail on the east side of what used to be a private ranch owned by the “poet of the Sierras’ Cincinnatus Joaquin Miller. Near the crest of a ridge overlooking the bay, among a grove of redwoods, was an odd plaque embedded in concrete that was all but unreadable. Using a cheap digital camera, I took home over a dozen images of the plaque having no idea what it said as the surface had been badly defaced by graffiti. It became clear that the plaque had been intentionally abandoned by park officials. Even its location near a well organized trail was intentionally blocked by wooden rails that left casual guests unaware of its existence.

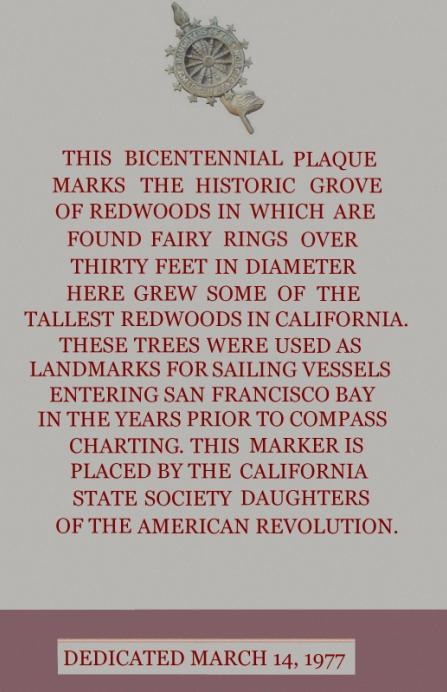

After hours of work, the plaque’s secret was reconstructed using nearly all of the images I’d taken. And what a surprise, as the words launched this quest to uncover the mystery of the defaced plaque. The words of the plaque were dramatic. It didn’t take long for me to find out what a “Fairy Ring” was, the saplings that grow into 2nd or 3rd growth trees that spring up from the stump of a dead redwood tree.

After hours of work, the plaque’s secret was reconstructed using nearly all of the images I’d taken. And what a surprise, as the words launched this quest to uncover the mystery of the defaced plaque. The words of the plaque were dramatic. It didn’t take long for me to find out what a “Fairy Ring” was, the saplings that grow into 2nd or 3rd growth trees that spring up from the stump of a dead redwood tree.

After reconstructing the plaque placed there by California’s Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR), I realized it had been enshrined by a large number of redwood branches that were meant to highlight the size of one of the two trees (more later) used by ships to navigate when they entered the bay during the first half of the 19th century. But why the horrific condition of the plaque or the lack of any information about it online?

Aroused by the intersection of conflicting information, I learned online that the entire park and surrounding area was made up of second and third growth redwood trees, with only a single old growth redwood surviving in the East Bay. The monument (also done by DAR) to the right commemorates what some people call “Grandpa” located at Leona Heights Park, across from Merritt College. Grandpa is over 485 years old and incredibly hard to get to. It is badly stunted, only around 100 feet in height. Its size and location just off of a cliff played a role in why it survived, as all other old Redwoods in the area were cut down, with the last major clear cut that was used to rebuild San Francisco after the 1906 San Andreas quake.

Aroused by the intersection of conflicting information, I learned online that the entire park and surrounding area was made up of second and third growth redwood trees, with only a single old growth redwood surviving in the East Bay. The monument (also done by DAR) to the right commemorates what some people call “Grandpa” located at Leona Heights Park, across from Merritt College. Grandpa is over 485 years old and incredibly hard to get to. It is badly stunted, only around 100 feet in height. Its size and location just off of a cliff played a role in why it survived, as all other old Redwoods in the area were cut down, with the last major clear cut that was used to rebuild San Francisco after the 1906 San Andreas quake.

The California Redwood Story

Back in 1831, the botanical explorer, David Douglas visited a Redwood grove near Santa Cruz. In a letter to a friend he wrote about them: …”which gives the mountains a most peculiar, I was almost going to say awful, appearance, something which plainly tells we are not in Europe.”

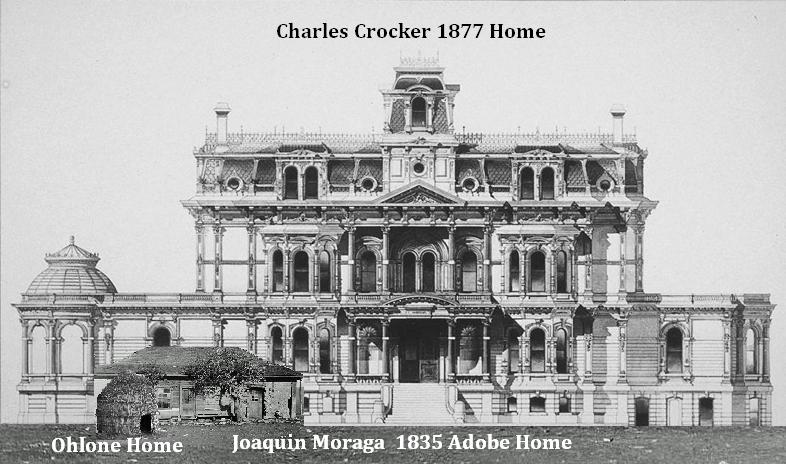

The bay area’s first homes were made out of woven reeds. Then came the Spanish with their Adobe homes of mud bricks, that used only a small amount of wood for rafters, finally the tree house people from Europe (half of Europe’s original forests had been cut down by the middle ages) started to arrive, with trappers like the Russians in 1812 at Fort Ross, inland to Sutter’s Fort, which they leased to John Sutter in 1840. With the arrival of the masters of the axe in 1846 (90% of the U.S. original forests are gone) the housing boom would explode as woodsman saw only dollar signs in the giant coastal forests.

Joaquin Moraga’s father co-founded San Francisco in 1776. Charles Crocker co-founded the Central Pacific Railroad Company.

Joaquin Moraga’s father co-founded San Francisco in 1776. Charles Crocker co-founded the Central Pacific Railroad Company.

California Redwood History

The coastal redwood (sequoia sempervirons) has an ancestral line dating back to the Jurasic era 200 millions years ago that included Europe and Asia. Its most recent relationship with humans spans thousands of years with the California’s First Nations. See Part II for a variation on this history.

The coastal redwood (sequoia sempervirons) has an ancestral line dating back to the Jurasic era 200 millions years ago that included Europe and Asia. Its most recent relationship with humans spans thousands of years with the California’s First Nations. See Part II for a variation on this history.

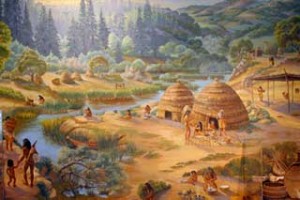

Most of California’s tribal communities, just as other plants or animals lived near but not within redwoods groves. The East Bay’s first people lived in small bands on the flat lands and slopes of the hills of Richmond, through Strawberry Creek in Berkeley, to Oakland. The Huichiun (Ohlone) people lived on the west side side of the hills while the Joaqium and Saclan (Miwok) lived inland on the west side. Not a lot is known about the Huichiun bands. They and all other bands were commonly called “Diggers” by Yankees as many tribal people took part in the Gold Rush. One of the last women who still spoke her own language in the 1920’s and been alive during the Spanish era remembered the large annual gatherings of the bands every spring in Richmond that white people called Digger Fandangos.

The Coastanoan (Ohlone) people that stretch from Monterrey to the East Bay held spiritual practices (Kuksu) that included the prominent use of Shellmounds where their ancestors and one of their primary food sources (shellfish) are buried. Their migratory existence revolved seasonally around the water flow of creeks and streams with their homes made of reeds but did incorporate redwood bark

The Coastanoan (Ohlone) people that stretch from Monterrey to the East Bay held spiritual practices (Kuksu) that included the prominent use of Shellmounds where their ancestors and one of their primary food sources (shellfish) are buried. Their migratory existence revolved seasonally around the water flow of creeks and streams with their homes made of reeds but did incorporate redwood bark

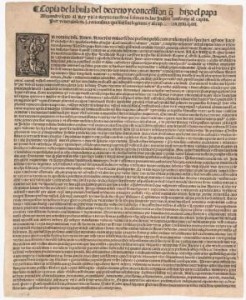

The year following the discovery of the new world, Pope Alexander VI published a Papal Bull known today as the “Doctrine of Discovery“, that when combined with Pope Nicholas V’s 1452 Bull which decreed that the pagan world would be divided between Portugal and Spain to conquer, consigning them to “perpetual servitude“. Spain was given the western hemisphere land. Some of us are awaiting for these decrees to be withdrawn, apologies made and the full impacts of all broken treaties assessed based on over 500 years religious wars.

In 1532, the Spaniard Hernán Cortés laid claim to California, but colonization above Baja California was delayed until 1769 due to harsh currents and it’s distance via ship from the rest of the world. Don Gaspar de Portolá, the Military Governor of California led the expedition that discovered the San Francisco Bay, as part of their plans to identify a mission at Monterrey. In the trek up to the bay, Portolá’s group first spotted redwoods, naming one particular tree Palo Alto (the Spanish translation is High Tree) where the city now resides.

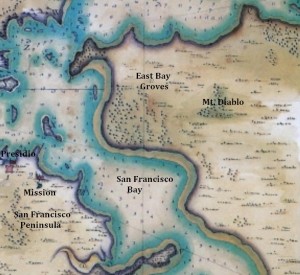

After Spain setup a mission in Monterrey in 1769, explorations of the bay took place with the goal of creating a mission there. In 1772, Father Juan Crespi created several maps of the San Francisco Bay that showed the entrance to the bay. One of the maps he drew included very rough sketches of the San Antonio Creek and San Leandro Bay. And to the east of these two bodies of water he drew in the “Bosques” of the Contra Costa range.

During the March 1776 expedition to found Mission San Francisco de Assisi and the presidio, Lieutenant–colonel Juan Bautista de Anza would explore the east bay’s redwood covered ridges of the Oakland Hills. On March 30th 1770, Father Font documented the size of the Palo Alto redwood tree, estimating it to be 50 varas in height (a vara is 3 inches short of a yard) with a circumference of 5.5 varas. He was also told by the expedition’s soldiers that there were much larger redwoods in the nearby hills. During their exploration of the East Bay that had the goal of seeking a route to the north bay, they spotted “buros” with 2 vara long antlers that were too fast for them to capture near a grove of trees. In September when the Spanish ship San Carlos arrived, its navigator Canizares drew up a map of the bay that showed the east bay Oak forest and trees in the hills of the East Bay.

Since the Spanish used adobe to construct their buildings, other than rafters for their roofs, there was little interest in logging redwood trees in the bay area until the 1830’s. With the arrival in 1812 of the Russians around Fort Ross redwoods were logged and used. With the Santa Cruz holding most of the redwoods it was this area up to Redwood City in San Mateo along with Mill Valley in Marin County where mills started to show up as a handful of French, British and Americans arrived.

Part I – General Redwood Factoids:

In l900, an acre of old growth redwood sold for $100.or less. Between 1940 and 1960, the price was $500 to $1,000 an acre. In 2002 it cost the public $64,000 an acre to regain control of the last uncut groves in the Headwaters.

Imagine ripping apart the Sistine Chapel and selling its walls as tourist trinkets in contrast to placing a price on a 2,000 year old growth redwood tree.

There used to be 1.9 million acres of old growth redwoods, along 450 miles of the coast from Monterrey to Oregon. Today, only 68,000 acres (3.5%) are left. In 1886, the Elk River Lumber Co.claimed it cut down a 424 feet high redwood. Many of the ancient trees regularly reached over 300 feet (Wikipedia says the tallest was the 379 foot high Hyperion). While the biggest Sequoia is the General Sherman tree. In 1934, one Humboldt County redwood, according to the source was 2,200 years in age when felled up in the Avenue of the Giants.

Redwood saw mills sprung up from Fort Ross to Santa Cruz. Towns like Redwood City or Mill Valley (much of Mt. Tamalpais was stripped bare of its forests) were named for their operations, while Santa Cruz was the largest bay area lumber producer (28 sawmills by 1868 with nearly 100 redwood mills statewide) for the San Francisco market until the 20th century.

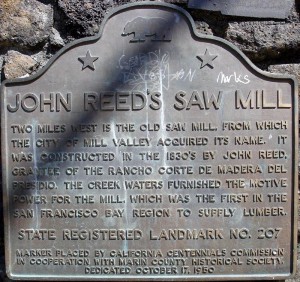

Very few trees were taken by the Spanish, which actually banned Ohlone people from burning them. Due to their size only a few trees were cut prior to California becoming a state (see Part II for details on Oakland’s saw mills). The first saw mill was the 1834 Lassen mill in Santa Cruz with another constructed in Mill Valley by the American John Reed two years later.

This changed overnight with the Gold Rush and San Francisco’s dramatic growth, as the city was destroyed seven times by fire in a few years, driving up lumber demand.

All of the old growth in Marin, San Mateo, Napa and the East Bay was gone by 1920 except for Muir Woods. Protection of old growth in Santa Cruz started in the 1860’s. The felling of redwood increased from 107 million to 224 million board feet a year between 1866-1880. Using ever more sophisticated techniques like steam donkeys 500 million board feet a year was cut during the early 20th century. The U.S. Forest Service (they were originally called the Bureau of Forestry) was reorganized in 1901 to support the management of harvesting of lumber. John Muir’s work with Teddy Roosevelt helped accelerate the interest and concern over redwoods and sequoias that had been around since the 1850’s after the indecent destruction of the Discovery Tree. In 1900, the Bureau of Forestry did the first study on the potential for future sustained-yield operations.

A 1922 newspaper article claimed that 2 million acres of California’s trees were cut down, with over 400,000 acres being Redwoods. At that time 6,500 acres of Redwoods were being chopped down every year. One report said that over 86,000 acres of privately held Redwood land had been turned into livestock pasture, while another source claimed that much of the East Bay acreage had been dynamited to remove the stumps. Dynamite was routinely used to blow up redwood logs into smaller pieces during the early days.

The 1922 article boasted that southern California alone used twice as much lumber as the rest of country combined per year. It estimated that there was 13 million acres of trees equal to 313 billion board feet of merchantable lumber in the state of which 72 billion board feet was Redwood. By the latter end of the 1940’s over 109,000 acres of trees a year were logged annually.

The Spanish Missionaries at San Francisco de Assisi did not exploit the giant trees, even banning Ohlone tribes from their practice of burning the woods.

The first organized saw mill in the bay was started by the American John Reed in 1836 at Mill Valley that would soon be followed by massive logging operations From Redwood City to the Oakland hills that denuded Mt Tamalpais and all the other ridges of the bay of its original giants. Except for a few spots like Muir Woods.

The first organized saw mill in the bay was started by the American John Reed in 1836 at Mill Valley that would soon be followed by massive logging operations From Redwood City to the Oakland hills that denuded Mt Tamalpais and all the other ridges of the bay of its original giants. Except for a few spots like Muir Woods.

Today, there is less than 5% of the original old growth Redwoods left. Thanks to the modern environmental movement in California, campaigns by groups like Earth First! played a key role in bringing the destruction of the last old growth stands in Humboldt county after a Texas millionaire took control of the Pacific Lumber Co. and nearly cut down the state’s last remaining privately held old giants. The battle would peak in May 1990 when two prominent Earth Firster’s were charged by federal authorities for attempting to commit suicide when a bomb planted by unknown pro-lumberites nearly killed them. They were eventually found innocent, yet no attempts to find the criminals was carried out. The bombing would play a major impact on the radical wing of the environmental movement as federal authorities carried out a campaign to crush the movement that had spread across the western half of the country.

Redwood Protection History

The Spanish that arrived in the state in 1769 never fancied any serious logging of Redwoods and even banned tribal people from burning forest areas. Early American logging practices, combined with the size of the early old growth trees limited cuts down to areas mostly between Monterrey to San Mateo, while the major forests to the North were left untouched until their discovery in the early 1850’s.

The campaign to save the Redwoods started in 1867 when JW Welch decided against logging 350 acres of old growth Redwoods on his property. A photographer named Andrew Hill attempted was run off Welch property made a speech at Stanford that led to the formation of the Sempervirons Club that pushed the purchased the Welch Grove around Santa Cruz in 1901 to form the 3,800 acre Big Basin Park at a cost of $250,000 (only about 1,300 acres were virgin redwood).

The campaign to save the Redwoods started in 1867 when JW Welch decided against logging 350 acres of old growth Redwoods on his property. A photographer named Andrew Hill attempted was run off Welch property made a speech at Stanford that led to the formation of the Sempervirons Club that pushed the purchased the Welch Grove around Santa Cruz in 1901 to form the 3,800 acre Big Basin Park at a cost of $250,000 (only about 1,300 acres were virgin redwood).

In 1874, a colonel Armstrong living in the Russian River decided hold onto 440 acres of Redwoods that he tried to but failed to give to the state for protection in 1890. Sonoma county purchased the tract for $70,000 in 1934 when it finally turned into the Armstrong State Park.

The state created a forestry board in 1885, and the first version of the Forests Practices Act in 1947 that required leaving four seed trees per acre.

The state created a forestry board in 1885, and the first version of the Forests Practices Act in 1947 that required leaving four seed trees per acre.

In 1907 a Marin water company proposed damming Redwood Creek which would have flooded the last stand of old Redwood trees in the county. Congressman William Kent purchased 611 acres of land and donated it to the federal government, with President Roosevelt turning it into the first Redwood National monument the following year. Kent refused to let the park be named after him and instead pushed for it to be named after John Muir, known as the Muir Woods National Monument today.

The state’s most prominent Redwood park campaign started in 1919 with the formation of the Save-the-Redwoods League that was led by a number of prominent men, including Dr. Merriam from the University of California. The Humboldt Redwood State Park was formed in 1921, after the purchase of three different major groves covering over 50,000 acres of land. In the famous Founder’s Grove next to the Avenue of Giants one of the largest trees ever was cut down soon after its discovery.

In 1920, a federal study was done to investigate the possibility of a National Redwood park. Nothing came of the work done by the the Save the Redwoods people until 1968.

Saving Oakland’s Redwoods

The history of protecting Oakland’s Redwoods can be traced back to 1855 when William P. Gibbons (b. 1812) first visited remains of the San Antonio redwood grove. William was a founding member of the California Academy of Natural Science, and a practicing medical doctor who came to San Francisco in 1853 from Delaware. He moved to Alameda where he lived until 1895 when his home was possessed by a local bank, dying a bit over a year later on May 18th, 1897. On June 4th 1867 William made a presentation before the Academy calling on the organization to take steps to protect what was left of the grove. In that presentation he made an impassioned plea to save what remained of the grove that included 1 million saplings, a few still standing old growth trees and stumps:

“On this little range of less than a half a mile square, there are probably not less than 1,000,000 of sapling redwoods. That which civilized vandals have left is fast becoming the prey of reckless squatters. Every year diminishes the number of stumps, which these fellows work up into firewood. In doing this they destroy such an immense number of the saplings that in a short period every vestige of this luxuriant nursery of the primeval forest will be obliterated, if measures be not taken to prevent it. A trifling sum would secure title and possession. There is no spot about San Francisco that possesses such admirable adaptations for a botanical garden. Every variety of tree and plant which grows in the State, or which flourishes to the north of us, would here find a congenial soil and climate. Already over fifteen species of forest trees are thriving within the district; there are over twenty species of shrubs, and more than three hundred flowering plants. With such a fair beginning initiated by nature herself, let the Academy make a move to secure this locality. It is not a question of local, but of general interest. The cause of science and of civilization demands that a conservative intervention should be made, that our noble forests may not be recklessly and permanently destroyed. That hill, with a little aid from the restorative processes of art, would be so regenerated in a few years as to become one of the most interesting localities in the United States.“

William said that there was stump and fairy ring still surviving 32 feet in diameter as well as dozens of others from 18-20 feet across.

“The Doctor has with great labor and taste completely restored — on paper — the main groups of these fallen giants, and has also made accurate drawings of the few trees yet spared by the woodman’s axe.”

Sadly, it is more than clear that the Academy failed to heed William’s warnings, even though his presentation did make it into Oakland’s centennial coverage of the city’s history in 1876. It would fall upon Joaquin Miller (known as the Poet of the Sierras) to preserve what was left of the grove. Miller would sell his famous log cabin in Washington D.C. and use the money to purchase the 70 acre “Hights” in 1886 along the old logging road that is now known as Joaquin Miller Road. While living at the Oriental House in Oakland’s Chinatown, he would started work his home and other monuments on the property, including planting 75,000 trees. In 1919, the city of Oakland purchased the property, six years after Joaqin’s death, allowing the family to stay on the property.

Two of the most powerful real estate barons in the east bay got the bright idea of buying up all of Oakland’s hills and then planting quick growing Eucalyptus trees as a business venture. Frank Havens and Borax Smith formed the Reality Syndicate, planting upwards of 8 million trees, only to realize that they were not good lumber trees. Smith who also owned the People’s Water Company, lumber companies up north and much of the trolley system in the East Bay would have a falling out with Havens, who passed away in 1917.

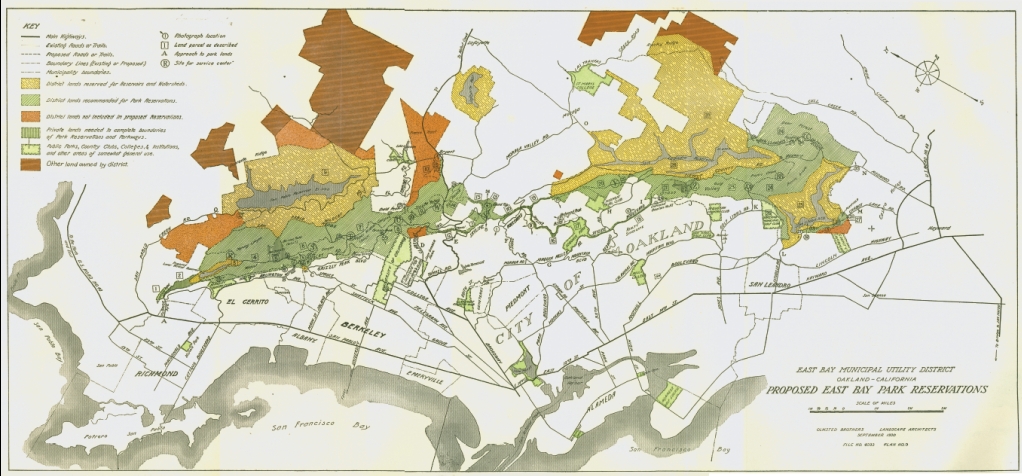

Proposals for developing an East Bay park system started to get organized in 1915. In March of 1922, under pressure from women’s clubs and the city’s park and recreation department, the board of supervisors agreed to hold an August 29th vote on the plan. The public voted in favor of moving ahead with a park. Finally, on January 19th, 1924 the city of Oakland condemned the 180-acre Frank C. Havens tract that included the Eastern half (including Redwood Peak) of the original San Antonio redwood grove. The new park planned for the land included a golf course and the city’s zoo, both of which never happened. The purchase of the park was soon followed by plans to create a much larger regional park.

Frederick Law Holmstead, the head of the newly formed state park system in 1928 was given $12 million to investigate and buy lands produced a major report with 18 major concerns. He also said:

“But if any of the future generations, for thousands of years to come are to have an opportunity of enjoying the spiritual values obtained from such primeval forest; this generation must exercise the economic self-restraint necessary for passing on some portion of this inheritance instead of cashing in on all of it.”

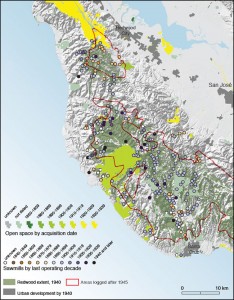

A six year campaign to build the East Bay Regional Park System ensued, with the public voting to initiate a large public park on November 9th, 1934. The first purchase of 2,166 acres took place on January 10, 1939 from the East Bay Municipal Utility District that took over the east bay’s private water companies back in 1923. Bonds were issues in 1927, 1938, 1945 and 1964 to expand the park.

A six year campaign to build the East Bay Regional Park System ensued, with the public voting to initiate a large public park on November 9th, 1934. The first purchase of 2,166 acres took place on January 10, 1939 from the East Bay Municipal Utility District that took over the east bay’s private water companies back in 1923. Bonds were issues in 1927, 1938, 1945 and 1964 to expand the park.

As of 2016, there are over 65 different parks in the 120,000 acre system that includes the Redwood Regional Park, Joaquin Miller Park and Robert’s Recreational Area (named after Thomas J. Roberts, a union organizer that played a crucial role in getting public support for winning the 1934 vote. Tommy was also the park’s director from 1939-1959. The above three parks contain all of the original Spanish lands where estimated 5 square miles of old growth Redwoods that were all cut down except a single tree between 1846-61 by American loggers.

Helen Gatagan Douglas’ proposal for a 2.4 million acre Roosevelt Memorial Forest statewide initiative with an estimated cost of of over $400 million (heavily fought by the lumber lobby) failed in 1949.

Helen Gatagan Douglas’ proposal for a 2.4 million acre Roosevelt Memorial Forest statewide initiative with an estimated cost of of over $400 million (heavily fought by the lumber lobby) failed in 1949.

In 1949, the state purchased 47,000 acres for about $1.5 million in an area extending east from Fort Bragg in Mendocino County and now know as Jackson State Forest. An additional 5,000 acres of a federal recreation demonstration area was given to the State of California that time, which then contained about 6,000 acres of virgin forest.

In 1949, the state purchased 47,000 acres for about $1.5 million in an area extending east from Fort Bragg in Mendocino County and now know as Jackson State Forest. An additional 5,000 acres of a federal recreation demonstration area was given to the State of California that time, which then contained about 6,000 acres of virgin forest.

It wasn’t again until the mid 1960’s when another wave of protection took off that finally included the formation of the Redwood National Park in 1968. After 60 years, the Save-the-Redwoods League with the help of the Sierra Club, and the National Geographic Society were able to get congressional support for the bill that was was signed by President Lyndon Johnson on October 2, 1968.

During much of the 20th century the logging industry grew in its power to counter any attempts at saving the redwoods. There was an earlier reason for why this was. Starting in the 1880’s a Scottish and American syndicate was setup to take over the redwoods in Northern California. The privatization of all of the redwoods was of course all about financial alliances that made sure that the trees were on the chopping block. Lobbying battle after battle during the last century to save the environment was always would always face coordinated campaigns just as the current Trump and the GOP era announced plans to privatize all of the National parks in the country.

During much of the 20th century the logging industry grew in its power to counter any attempts at saving the redwoods. There was an earlier reason for why this was. Starting in the 1880’s a Scottish and American syndicate was setup to take over the redwoods in Northern California. The privatization of all of the redwoods was of course all about financial alliances that made sure that the trees were on the chopping block. Lobbying battle after battle during the last century to save the environment was always would always face coordinated campaigns just as the current Trump and the GOP era announced plans to privatize all of the National parks in the country.

Starting in the mid 1980’s a new era of activism around the Redwoods was launched by the direct action group Earth First! At the time concerns about the last major groves in Humboldt County took off. From tree sitting to spiking activists were confronting lumber companies that were dead set on wiping the last old growth Redwoods. Earth First! activists Darryl Cherney and Judi Beri were arrested by the FBI for attempting to commit suicide when a bomb in their car nearly killed both of them (Judi eventually died of her wounds). The agency had been harassing and infiltrating the group the group for years. Even though they were exonerated, the FBI has never seriously attempted to find the perpetrators even though activists found nails exactly like those used in the bomb up at Pacific Lumber Co. where numerous threats against activists had been coming from.

Following the Julia Butterfly affair, where she spent two years in a 1,500 year old redwood she named Luna, Diane Feinstein negotiated a deal worth $480 million to purchase 7,472 acres of the Headwaters redwood grove and 11 others smaller sites at a price of over $64,000 an acre, a far cry from when privateers bought them for $100 an acre or less. A decade later, Maxxam had gone bankrupt. During the bankruptcy trial last year, a new company formed by Donald and Doris Fisher, the billionaire San Francisco founders of retailer Gap, acquired all 211,000 acres of Pacific Lumber’s land and its historic sawmill in the town of Scotia.

Following the Julia Butterfly affair, where she spent two years in a 1,500 year old redwood she named Luna, Diane Feinstein negotiated a deal worth $480 million to purchase 7,472 acres of the Headwaters redwood grove and 11 others smaller sites at a price of over $64,000 an acre, a far cry from when privateers bought them for $100 an acre or less. A decade later, Maxxam had gone bankrupt. During the bankruptcy trial last year, a new company formed by Donald and Doris Fisher, the billionaire San Francisco founders of retailer Gap, acquired all 211,000 acres of Pacific Lumber’s land and its historic sawmill in the town of Scotia.

Today, about 200,000 acres of virgin commercial forest remain, mostly in the northern Humboldt and Del Norte Counties.

Today, the bay area contains less than 11,000 acres of old growth redwoods with 10,800 of those located at Big Basin State Park and just one tree in the East Bay. Note work… Finished product will require recovery of loss of several hours of detailed research work on the annual tree production from the 1880’s onward that was lost thanks to attacks on the website while this research was being completed.

Today, the bay area contains less than 11,000 acres of old growth redwoods with 10,800 of those located at Big Basin State Park and just one tree in the East Bay. Note work… Finished product will require recovery of loss of several hours of detailed research work on the annual tree production from the 1880’s onward that was lost thanks to attacks on the website while this research was being completed.

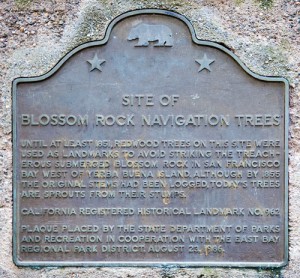

But here’s where the story gets messy. An online search for the significance of the plaque showed a state marker located at another Oakland Hills park called Robert’s Recreational Area, rather than Joaquin Miller park. The state historic marker titled “Blossom Rock Navigation Trees” is due east of the old plaque at the 82 acre Roberts park that was adopted in 1979 by Kaiser Aluminum & Chemical Corporation after Oakland ran short of funds for the East Bay Regional Park system (anybody remember Prop 13?). You must pay to enter Robert’s which has a huge parking lot, swimming pool, picnic areas and the marker constructed in 1986 (nearly a decade after the original plaque), claiming that this park was where the Two Navigation Trees were located.

But here’s where the story gets messy. An online search for the significance of the plaque showed a state marker located at another Oakland Hills park called Robert’s Recreational Area, rather than Joaquin Miller park. The state historic marker titled “Blossom Rock Navigation Trees” is due east of the old plaque at the 82 acre Roberts park that was adopted in 1979 by Kaiser Aluminum & Chemical Corporation after Oakland ran short of funds for the East Bay Regional Park system (anybody remember Prop 13?). You must pay to enter Robert’s which has a huge parking lot, swimming pool, picnic areas and the marker constructed in 1986 (nearly a decade after the original plaque), claiming that this park was where the Two Navigation Trees were located.

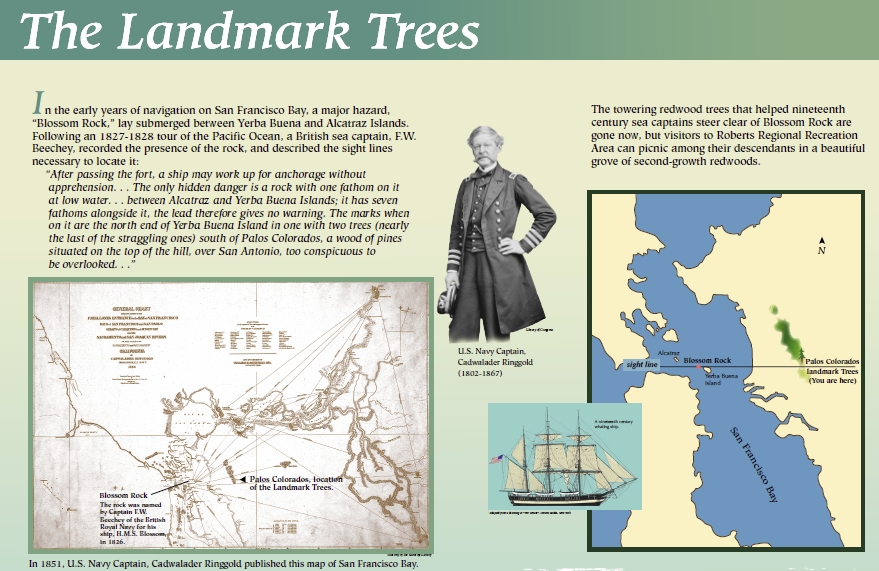

Near this plaque were two others, a recent plaque having nothing to do with the redwoods placed there by World War II veterans and then the below presentation about the trees:

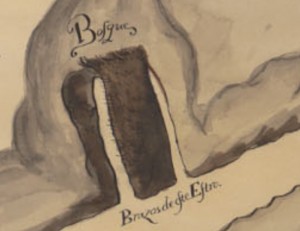

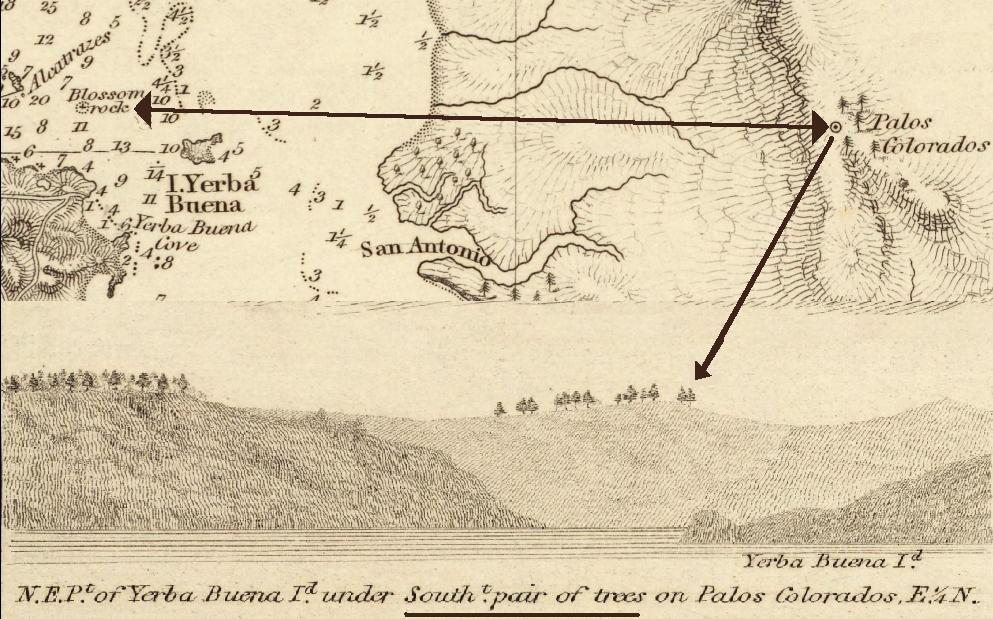

What’s more than a bit odd, is that the plaque gives apparent credit to the English explorer, Captain Frederick Beechey for identifying the usefulness of the “Two Blossom Rock Navigation Trees” back in 1826 but then uses an 1851 navigational map by an American Navy Captain. Maybe its just the fact that the original English map is too complex for American tourists, as it also shows details of the two navigational trees, plus what appears to be many more redwoods. Below is an enlarged section of Beechey’s original navigational chart from the expedition that was published in 1833 with its fathom markers removed. The bottom half of the image is the line of sight drawing from Blossom Rock in San Francisco Bay of the trees at Palos Colorados lined up with the Northeast tip of Yerba Buena (Goat) island. It should be noted that Beechey’s navigational chart along with the drawings validates the authenticity and location of the Blossom Rock trees’ location and their importance. The 1826 drawing takes on even more importance as it is the oldest visual documentation of the other giant redwoods near the two navigation trees, but also for an even larger grove to the north. Note that you will need to click below on the bold gray bar title “Will the Real Blossom Rock Navigating Trees Please Stand Up” to see the Beechey Chart and drawing.

What’s more than a bit odd, is that the plaque gives apparent credit to the English explorer, Captain Frederick Beechey for identifying the usefulness of the “Two Blossom Rock Navigation Trees” back in 1826 but then uses an 1851 navigational map by an American Navy Captain. Maybe its just the fact that the original English map is too complex for American tourists, as it also shows details of the two navigational trees, plus what appears to be many more redwoods. Below is an enlarged section of Beechey’s original navigational chart from the expedition that was published in 1833 with its fathom markers removed. The bottom half of the image is the line of sight drawing from Blossom Rock in San Francisco Bay of the trees at Palos Colorados lined up with the Northeast tip of Yerba Buena (Goat) island. It should be noted that Beechey’s navigational chart along with the drawings validates the authenticity and location of the Blossom Rock trees’ location and their importance. The 1826 drawing takes on even more importance as it is the oldest visual documentation of the other giant redwoods near the two navigation trees, but also for an even larger grove to the north. Note that you will need to click below on the bold gray bar title “Will the Real Blossom Rock Navigating Trees Please Stand Up” to see the Beechey Chart and drawing.

Not only does this single drawing open up a new mystery but it becomes the most important historic documentation of what happened to the Oakland Hills redwoods. To summarize, the last evidence of what may have been the largest redwoods in world can be summed up with Joanie Mitchell’s song, “They paved paradise and put up a parking lot” for where the real location of the Blossom Rock Navigation Trees is.

The Blossom Rock Navigation History

In an 1893 article published in Erythea (a University of California botany journal) Dr. William P Gibbons spoke of visiting the San Antonio Redwood Grove back in 1855. He described the size and contents of what is known today as Redwood Bowl in Roberts Recreation Area just below Redwood Peak, saying that he counted over 150 stumps, that were 12 to 21 feet in diameter, up to 8 feet off the ground. He was particularly fascinated with three trees that had coalesced together into a 57-foot-in-diameter stump. He identified the location as follows:

One particular portion of this redwood tract under discussion lies just below and to the westward of the highest point of the Oakland Hills. It occupies a small depression in the hill somewhat resembling a moraine, about two acres in extent.

One particular portion of this redwood tract under discussion lies just below and to the westward of the highest point of the Oakland Hills. It occupies a small depression in the hill somewhat resembling a moraine, about two acres in extent.

Today, there is a fairy ring just southwest of a cluster of cabins and a campfire with log stumps to sit on that matches the enormous size of his description. He describes the location of the largest redwood he saw in the San Antonio Grove, a grove that exists today as 3rd growth redwoods in Joaquin Miller Park a half mile southwest from Redwood Peak:

Entering the hollow, one finds himself within an area circumscribed by a wall of solid wood, the ‘greatest diameter of which is thirty-two feet at a distance of four feet from the ground; this measurement not including the bark, which would raise the diameter to thirty-three and a half feet.

And with the above description, we have what our experts claim to be the location of at least one of the two Blossom Rock Navigation trees where a plaque was placed in 1977. However, as part I of this piece points out, there are two competing plaques less than a few hundred yards apart claiming to be where at least one of the trees once existed, yet in two different parks on each side of Skyline Boulevard. And as a result, it has ever more become my own opinion that to read the work encompassed here in this piece should require the same kind of initiatory requirements – respect for the natural world – as the First Nations people had.

Will the Real Blossom Rock Navigating Trees Please Stand Up

When first starting out on this quest to find out why the plaque at Joaquin Miller Park had been so mistreated, it wasn’t my intention to throw out both locations, but after more than a bit of work, it is no longer clear to me exactly where the original Blossom Rock Navigation Trees were located.

The key segment of Beechey’s 1833 map is shown below with an arrow between Blossom Rock and the trees, but more important, his line of sight drawing that lines the trees up with the tip of Yerba Buena is also included. The map clearly shows that the rock doesn’t line up with the Northeast corner of Yerba Buena and the point identified as Palos Colorados. It is the lower drawing done by Beechey from Blossom Rock that shows the true alignment of Yerba Buena and the two giant trees.

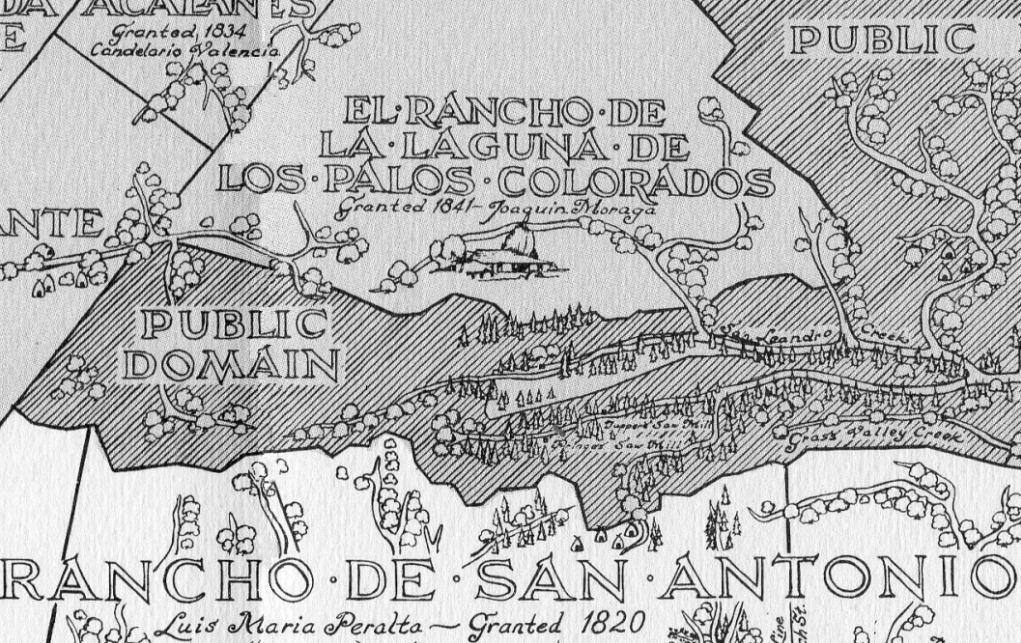

The bull’s eye used in Beechey’s map can be a bit confusing. The term Palos Colorados in the above map, was later used to identify the Rancho Laguna de los Palos Colorados. The 3,300-acre Rancho that was given to Joaquín Moraga and his cousin Juan Bernal by the Alta-California governor in 1841. So the bull’s eye in Beechey’s map in 1826 may only refer to the general Spanish term used for the redwoods (as note directly above with “South pair of trees on Palos Colorados”). Or it might also refer to the area because of the redwoods informally by locals prior to Moraga getting the land grant as the groves were well known by the local Spaniards since their own arrival in the 1770’s.

The bull’s eye used in Beechey’s map can be a bit confusing. The term Palos Colorados in the above map, was later used to identify the Rancho Laguna de los Palos Colorados. The 3,300-acre Rancho that was given to Joaquín Moraga and his cousin Juan Bernal by the Alta-California governor in 1841. So the bull’s eye in Beechey’s map in 1826 may only refer to the general Spanish term used for the redwoods (as note directly above with “South pair of trees on Palos Colorados”). Or it might also refer to the area because of the redwoods informally by locals prior to Moraga getting the land grant as the groves were well known by the local Spaniards since their own arrival in the 1770’s.

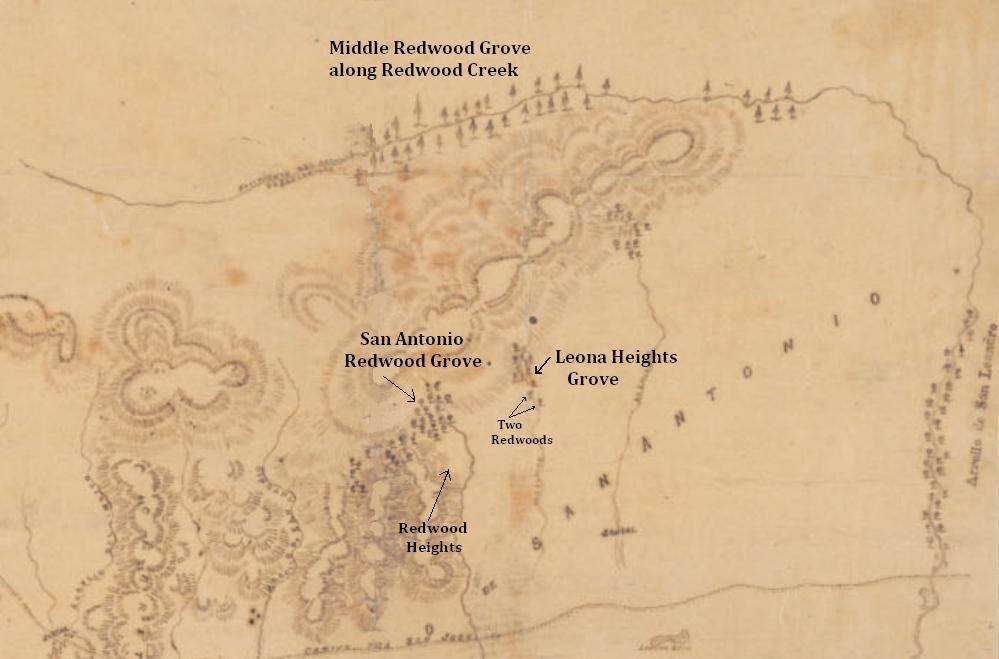

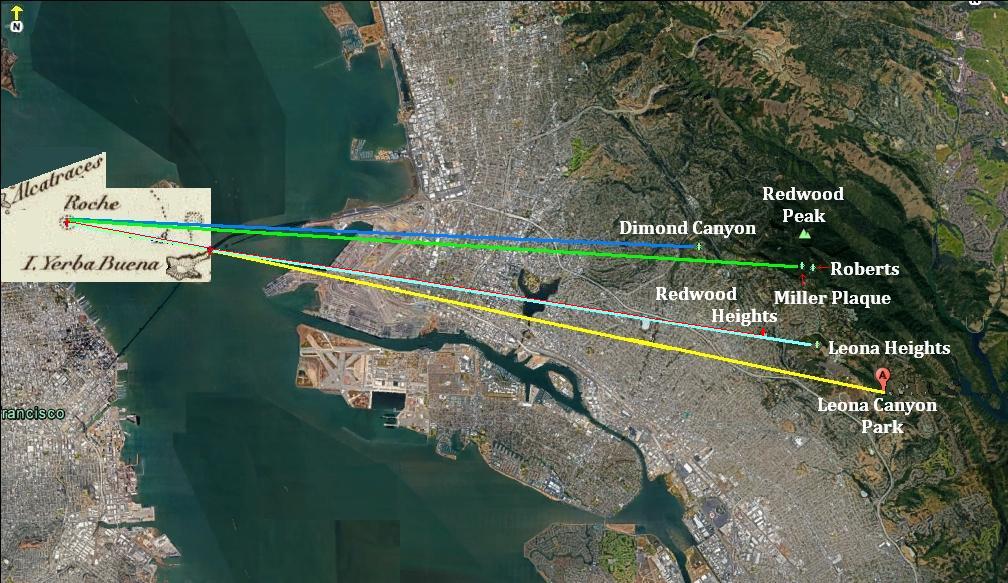

There can be no doubt that there were many very large trees in the East Bay hills. But only two trees could actually match the line of sight test when combined with an accurate map. The 1986 (California Historical Landmark #962) plaque located in Roberts Recreation area as well as an older 1977 plaque at Joaquin Miller Park are clearly in dispute, unless the published Beechey instructions for locating the trees was in error, or Yerba Buena Island (the Goat Island part of Treasure Island) has moved for some reason. Is it possible that Google Earth’s satellite maps are distorted? Unless something is terribly wrong with my ability to draw a straight line, Beechey’s instructions were clear, which means that the two Blossom Rock Navigation trees were not located near Redwood Peak. Below is a modern map showing the very real problem that brings the location problem into focus. This new map super-imposes the location of Blossom Rock and Yerba Buena for visual purposes, and then shows that all but Redwood or Leona Heights actually line up exactly as required by Beechey’s visual sight test. The two plaque antedates clearly don’t work and are too far north. Leona Canyon Park does but it also nearly a mile further away to the southeast.

This new map super-imposes the location of Blossom Rock and Yerba Buena for visual purposes, and then shows that all but Redwood or Leona Heights actually line up exactly as required by Beechey’s visual sight test. The two plaque antedates clearly don’t work and are too far north. Leona Canyon Park does but it also nearly a mile further away to the southeast.

A quick trip to all three of alternative locations suggests it would be entirely possible for any of the three locations to be where the real location of the two trees were. Redwood Heights as the first candidate is the shortest distance from the bay, but is also slightly below the ridge top compared to the San Antonio Grove. Three blocks below its peak is one of largest, most healthy redwoods in Oakland today, but the entire area, once known as Crocker Heights was stripped of its trees and turned into a moderately priced housing tract following World War II. And remnants of a surviving stump when the houses were built is likely to have been lost.

Leona Heights, where the last original old growth redwood still lives, when looking from the bay is just slightly higher in elevation than Redwood Heights, but again lower than the San Antonio Grove. The last of the three candidates, Leona Canyon is nearly at the same height as San Antonio but is also substantially farther away.

But the visit to the Leona Heights site took on an entirely new complication. Upon arrival, it was clear that there would never be a chance to find any possible remaining hints to its location as the entire location had been leveled and turned into a parking lot for Merritt College that was now abandoned.

According to one source, the two Blossom Rock Navigation trees were likely chopped down in 1854 as newer navigational technology replaced the line of sight process used by navigators to avoid the dangerous Blossom Rocks that could sink ships when they tried to land at Yerba Buena (now S. F.). In 1870, Blossom Rock was demolished (see a full report here). The two tree’s removal were never documented, however a June 1854 (see Alta article above) news article in the Daily Alta said that it was a matter of months before the San Antonio grove would been completely gone. This was followed by an August of 1855 article confirming that nothing was left. Another source said that Harry Meiggs’ company went after the biggest and best trees first, so they could have been chopped down as early as 1849.

William Gibbons spoke of large redwoods in other areas including Leona Heights. Even closer, and still directly on the appropriate line to match up with Beechey’s instructions includes Redwood Heights, which is just under a mile closer to Blossom Rock than Leona Heights. For example just off the very peak of Redwood Heights, on 39th Avenue, and just four blocks from one of the major logging roads originally used is one of the healthiest and largest redwoods in Oakland today. The top of Redwood Heights is another location for a smaller grove that could have been cut down prior to Gibbons visit to the area since he arrived in 1853, or nearly four years after logging in the hills began. Of all the candidates up in the hills, if there were large trees at Redwood Heights, they would represent the closest candidates for what is a very long way from Alcatraz to see the Navigation Trees. The above mentioned redwood on 39th Avenue is about a quarter mile below the summit of Redwood Heights to be a candidate. Sadly, the question of any documentation of very tall trees here would take a whole new series of investigations of housing records going back to the 1940’s when major development of housing took place, and even then, would contractors have taken note of any large stumps?

William Gibbons spoke of large redwoods in other areas including Leona Heights. Even closer, and still directly on the appropriate line to match up with Beechey’s instructions includes Redwood Heights, which is just under a mile closer to Blossom Rock than Leona Heights. For example just off the very peak of Redwood Heights, on 39th Avenue, and just four blocks from one of the major logging roads originally used is one of the healthiest and largest redwoods in Oakland today. The top of Redwood Heights is another location for a smaller grove that could have been cut down prior to Gibbons visit to the area since he arrived in 1853, or nearly four years after logging in the hills began. Of all the candidates up in the hills, if there were large trees at Redwood Heights, they would represent the closest candidates for what is a very long way from Alcatraz to see the Navigation Trees. The above mentioned redwood on 39th Avenue is about a quarter mile below the summit of Redwood Heights to be a candidate. Sadly, the question of any documentation of very tall trees here would take a whole new series of investigations of housing records going back to the 1940’s when major development of housing took place, and even then, would contractors have taken note of any large stumps?

In a segment of the 1853 Rancho San Antonio land map above, are actual trees located at Leona Heights that are clearly marked that could be the Navigation Trees. the San Antonio Redwood Grove is shown just below Redwood peak. Of special interest are the two trees located at Leona Heights that are aligned perfectly with Yerba Buena and Blossom Rock, making them a perfect match for Beechey’s line of sight method to avoid shipwrecking. The only other location that also triangulates with Blossom Rock would be a small grove located in Redwood Heights, due west (towards the bottom of the map) of the San Antonio Grove, or the much more distant Leona Canyon trees.

Along the line between Redwood Heights to Leona Canyon is where the best candidates for the site of the Blossom Rock Navigation trees can be found. The two trees documented in the 1853 map indicates Leona Heights as the place where a modest salutatory plaque should go, were it not for the final story, the laying in of a parking lot.

Back in 1969 at the height of the Black Panther movement that began in Oakland, the movement had as one of its primary organizing centers a small technical school known as Merritt College. In Oakland’s racist wisdom of the day, just as in San Francisco where the focal point of the Panthers was in the Western Addition, both areas were literally torn down (In S. F. the Victorian houses in the Western Addition used by the Panthers were condemned, put up on wheels and towed away). the earlier Merritt College, was shut down, and an entirely new and far more inconvenient location for the college was constructed by removing the entire ridge top of what had once been Leona Heights. here, around 1854, in one of those very magical visionary spots of the bay, now obscured by the bushes of the abandoned student parking lot, were located a couple of the largest redwoods ever, trees that may have lived for maybe two thousand years or more before being torn limb from limb by a bunch of gold digging Yankees .

Most historic pieces suggest that redwoods were not targeted as a source of profit until the arrival of Americans in 1846. There is evidence that organized logging in the East Bay happened as far back as the late 1790’s with two Missions (Santa Clara and Mission San Jose) were built with redwood from the San Antonio Grove. In 1820, Alta-California’s governor gave the 44,000-acre Rancho San Atonio to Luis Peralta as long as the church and other ranchers were allowed to cut redwoods, with the Middle Grove being open to common use. The push for cutting down the redwoods did not take off until after Gold Rush, with only a a few hand powered whipsaw mills in the bay area. The below composite map created by the National Park Service in 1936 shows where most of the logging took place, primarily on the public domain lands just west of Moraga and Bernal’s Palos Colorados Rancho. In the below compilation, two of the ten sawmills built by the Prince brothers and Tupper, as well as two bands of Huichui Ohlone villages can be seen. But after further work, its unclear if there were actually a lot more redwood groves than previously acknowledged when looking at Beechey’s 1826 drawings of the redwoods along the ridge tops.

In part II, the details of the mills and more will be covered.

In part II, the details of the mills and more will be covered.

See Part II for the conclusion of the lost history and the extended notes.