The below article appeared in the November 1980 It’s About Times – Abalone Alliance’s Newsletter

Jay Newbern

PG&E’s insistence on operating its Diablo Canyon nuclear power plant, located only two and a half miles from an earthquake fault, may seem like the epitome of madness. But twenty years ago, the utility was trying to site a reactor just 1000 feet from California’s most famous fault line — the San Andreas.

PG&E’s insistence on operating its Diablo Canyon nuclear power plant, located only two and a half miles from an earthquake fault, may seem like the epitome of madness. But twenty years ago, the utility was trying to site a reactor just 1000 feet from California’s most famous fault line — the San Andreas.

In 1958 PG&E proposed putting what would have been the world’s largest nuclear reactor to date on the coastline of Sonoma County. PG&E claimed that Bodega Head, a piece of land that juts into the Bodega Bay, was the one spot in the entire Bay Area where nuclear-generated electricity could be priced competitively with power produced by a conventional plant. It planned to complete the 330 megawatt reactor by 1966 at a cost of $61 million.

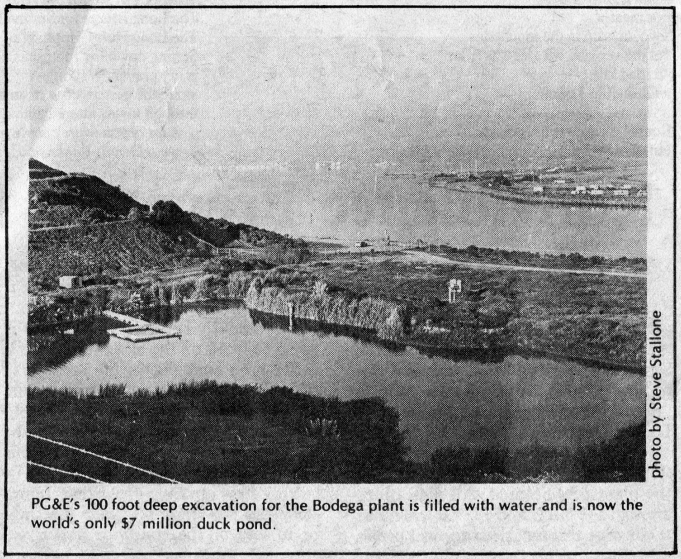

PG&E already owned 225 acres at Bodega Head and soon was able to get title to more. It obtained building permits on the basis that it planned a steam plant; nothing was mentioned originally about nuclear. A huge 100-foot deep hole was bulldozed out of the earth and concrete trucks began rolling through the small community of Bodega Bay, Before it was over, PG&E had poured $7 million of ratepayers’ money into the hole.

The first major problem discovered about the Sonoma site was that the nuclear plant was to be located only 1000 feet from the San Andreas fault zone. The Atomic Energy Commission,

predecessor of the Nuclear Regulatory Commission, declared that the distance must be increased — to 1320 feet. According to an eyewitness, the 1906 earthquake that wrecked San Francisco caused Bodega Head to ripple like a wave. At nearby Tomales Bay displacement of the earth was an amazing 20

feet.

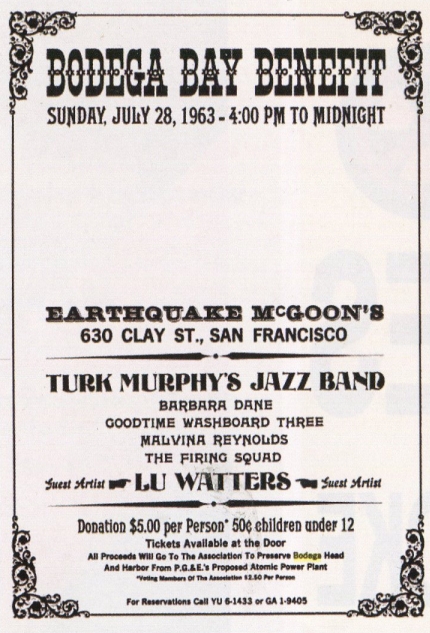

Opposition to the plant began in 1962 with a letter writing campaign by Karl Kortum, head of San Francisco’s Maritime Museum. David Pesonen, at that time a UC Berkeley law student, is credited by most as being instrumental, in the drive to preserve Bodega Head. Organized efforts soon arose.

The “Northern California Association to Preserve Bodega Head and Harbor” in Berkeley and the “Committee to Preserve Bodega Head” in Sebastopol led the fight against the Sonoma nuke, with public debates, lawsuits, petitions, letter writing, folksongs and rallies. Civil disobedience was not used. One of the groups’ publicity projects was the release of helium-filled toy balloons from Bodega. On them were printed: “This balloon could represent a radioactive atom of strontium-90 or iodine-131.” Several balloons were found in Marin County. The strong winds of Bodega Bay blow southerly toward San Francisco, only 50 miles away;

The “Northern California Association to Preserve Bodega Head and Harbor” in Berkeley and the “Committee to Preserve Bodega Head” in Sebastopol led the fight against the Sonoma nuke, with public debates, lawsuits, petitions, letter writing, folksongs and rallies. Civil disobedience was not used. One of the groups’ publicity projects was the release of helium-filled toy balloons from Bodega. On them were printed: “This balloon could represent a radioactive atom of strontium-90 or iodine-131.” Several balloons were found in Marin County. The strong winds of Bodega Bay blow southerly toward San Francisco, only 50 miles away;

A few politicians opposed the Bodega plant, including State Assemblyman Alfred Alquist (D-San Jose), US Interior Secretary Morris Udall, Public Utilities Commissioner William Bennett, the California Democratic Council and Governor Pat Brown. Only two small newspapers in the county, the Sebastopol Times and the Cloverdale Reveille, came out against it.

In 1956, two years before PG&E’s proposal was made public, the University of California had been negotiating for a Class A marine research station at Bodega Head. With its rich tide flats, tidepools in Horseshoe Cove, a bird habitat on land and a great variety of undisturbed ocean life outside the bay.

Bodega Head was considered the best site for a marine station on the entire California coast. But in 1957 UC withdrew in the face of PG&E interest and settled for a Class B site elsewhere in the headlands. The State Division of Beaches and the Sonoma County Board of Supervisors also refused to stand up to PG&E.

The California Public Utilities Commission was no better. Four out of five PUC commissioners announced that they would leave considerations of safety up to the Atomic Energy Commission. The AEC, of course, was committed to furthering the development of “peaceful use” of atomic energy and was hardly in the habit of denying nuclear licenses for any reason.

The US Geological Survey eventually agreed with environmentalists that the Bodega location was unsafe because of the nearby earthquake zone. After five years of battle, PG&E gave up on building a nuke at Bodega Head — only to settle soon after on the Diablo Canyon site.